Monitoring Change in Ulukhaktok

Members of the Ulukhaktok Aquatic Monitors & Observers, from left to right: Elder Director & Communications Lead, Allen Pogotak; Shore Safety Lead, Joey Pogotak; Program Lead and Field Researcher, Kitok Pat Akhiatak; Field Researcher and Cultural Advisor, Tony Alanak.

Ilitariyauyuq: Helen Drost

Above the surface, the Inuvialuit of the western Arctic face increasingly volatile ice and weather conditions in a region that is warming at four times the rate of the rest of the planet. Changes are also occurring below the waves at the base of the aquatic food web. The Arctic Ocean is absorbing heat as well as higher levels of carbon dioxide, which is causing the water to get hotter and more acidic. These changes are disrupting the species that are the foundation of Arctic marine ecosystems, including ice algae, zooplankton and small prey fish. How will this impact larger species such as fish and whales? And how can Inuvialuit communities use this knowledge to manage and adapt?

To address these pressing concerns, the hamlet of Ulukhaktok started an innovative, community-led monitoring program called Aquatic Monitors & Observers (AMO). The program monitors changes in the aquatic food web of their homelands, relying on elders and community members to guide a local team to collect data using state-of-the-art equipment.

The AMO team is comprised of local residents, hired by the Hunters and Trappers Committee (HTC). AMO team members are trained in the use of equipment and protocols to collect data on water quality and ocean conditions, as well as to collect photographs and video and record visual observations of key habitat sites.

The process starts with community input. Through a series of discussions, elders and community members identify priority locations for data collection, which are selected based on their value to the community for harvesting and cultural reasons. The AMO team then visits these key locations in small vessels and deploys CTDs—oceanographic tools that record salinity, temperature, turbidity, depth and oxygen levels up to 150 metres down the water column. The AMO team also collects underwater photographs and video using special remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). Visual observations are recorded, including nearby nesting sites of marine birds.

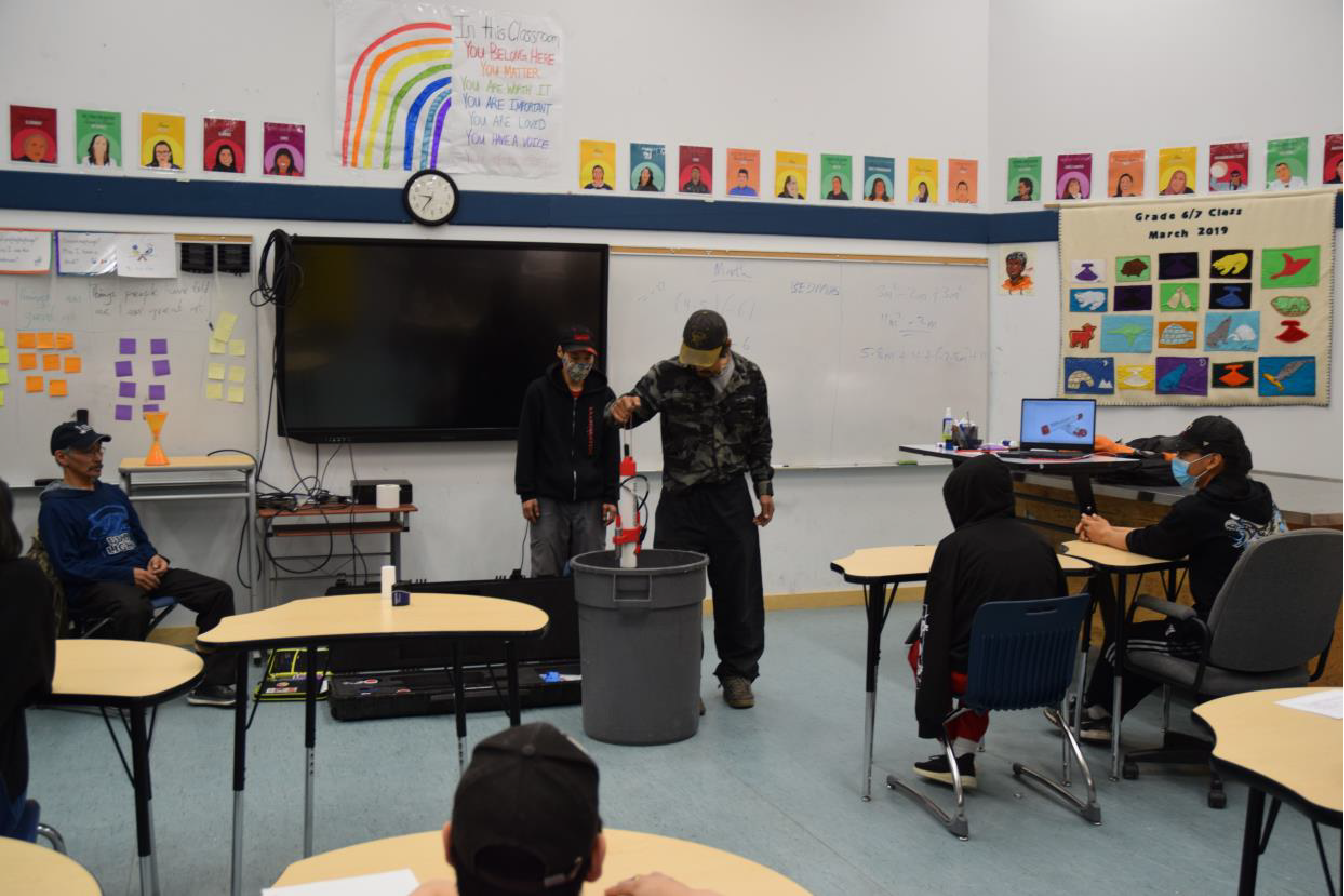

Members of the team visit the local school to talk about their work and demonstrate their equipment.

Ilitariyauyuq: Helen Drost

The AMO program is guided by the principle of community data ownership, which includes community control, access, possession, collaborative analysis and reporting of results. Both the Traditional Knowledge (TK) collected from elders and the analyzed field data are presented to the community and the HTC. Elders and harvesters help inform the analysis of the data collected, and workshops are held to encourage collaboration. Taken together, this information provides insight into the marine ecosystem in locations most important to the community.

As AMO team member Kitok Pat Akhiatak reflected:

“We are an Ocean People. Understanding the ocean and its inhabitants is important in keeping it for future generations to come. Bridging the gap between traditional knowledge and modern science will help us to understand the history and direction the ocean will take us. Aquatic monitoring and observing will also help us in being sovereign and bring a presence in the region, scientifically and traditionally.”

Analysis of the collected data is starting to reveal the tolerances and physiological limits of forage fish, a catch-all term for small fish species such as herring, capelin and Arctic cod. Forage fish are a major food source for bigger fish like Arctic char—a cornerstone of the local diet—as well as whales, seals and eider ducks. Over time, the local data can also be used to understand change and make projections about how the subsistence harvest may be affected by climate change and other stressors.

The program’s continued success is a testament to the community’s resiliency and capacity to adapt not only to climate change, but also to other unexpected events. The AMO team increasingly faces strong winds and stormy conditions, and fluctuations in the build-up of ice can make it hard to return to precisely the same location each time. These dynamics are also recorded by the AMO team. Recording ice and snow thickness, as well as the times and places when the ice forms and breaks up, helps the community improve the safety of their travel routes, including routes to key harvesting areas. During the pandemic, the team worked hard to continue the program. Trainings and team meetings were held online or by phone, while data collection trips were made independently.

Dr. Helen Drost, oceanographer and field program specialist, has been a driving force in establishing, training and supervising the AMO program and helping Sachs Harbour establish their own AMO program. With informed community consent, the teams are working with her to publish selected water quality data for public access.

Oceans North is proud to support to the AMO program. Oceans North staff member John Noksana Jr., an active harvester and former Inuvialuit co-management leader, has also provided invaluable guidance and communications support to both programs.

The AMO program actively maintains links to the Inuvialuit land claim organizations, created by the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA) with Canada. The AMO program regularly informs and seeks feedback by appearing before the Inuvialuit Game Council and the Inuvialuit Fisheries Joint Management Committee (FJMC). Initial funders of the program include the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC) and the Government of Canada.

Both AMO programs are seeking long-term, stable funding. Opportunities to strengthen the program have been identified. For example, access to better equipped, bigger vessels would increase safety for team members and help them to operate in volatile weather conditions.

Ultimately, the AMO programs seek to support and complement the expressed desire of the HTCs of Ulukhaktok and Sachs Harbour to designate their homelands as marine protected areas. This would provide them with more resources for monitoring and guardian-type programs. The knowledge gathered from monitoring could also be used to develop management and adaptation strategies. Amidst a changing Arctic, these communities deserve nothing less.

Paul Labun is Oceans North’s director of program development.