New Animated Video Highlights Importance of North Water Polynya

A variety of species depend on Pikialasorsuaq, also known as Sarvarjuaq or the North Water Polynya.

Credit: Oceans North Kalaallit Nunaat

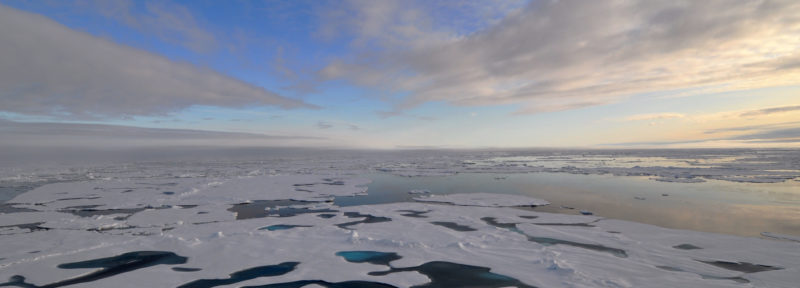

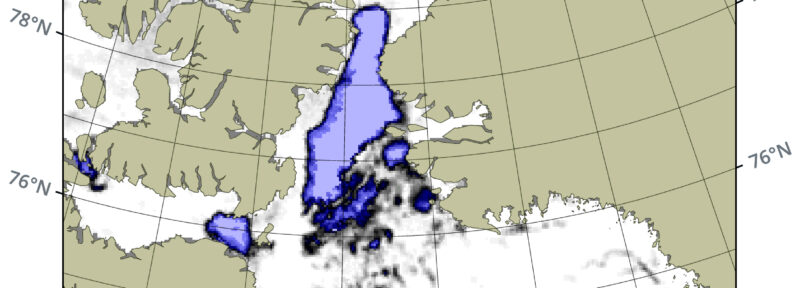

In the waters between Greenland and Nunavut, the Arctic’s most biologically rich polynya provides essential habitat for marine mammals, fish and seabirds each winter. Known as Pikialasorsuaq in Greenland, Sarvarjuaq in Nunavut and the North Water by others, this large marine oasis offers shelter as these creatures gather to feed, mate, spawn and overwinter.

Yet many people have never heard of a polynya, let alone Pikialasorsuaq. That’s why Oceans North Kalaallit Nunaat (ONKN), our sister organization headquartered in Nuuk, Greenland, has created a new animated video to raise public awareness about the importance of this region to Inuit communities in both Greenland and Nunavut.

“People were always asking, “What is a polynya and how does it work?” said Parnuna Egede Dahl, a special advisor with ONKN. “We wanted to answer those questions and explain why it’s so important to protect and manage this area.”

Using simple, animated graphics, the video illustrates how the North Water Polynya—an open area of sea water, surrounded by ice—forms each winter. An ice bridge emerges during the cold months as Nares Strait freezes between Canada and Greenland, blocking the flow of ice into northern Baffin Bay. The video shows how strong north winds then push ice out of the area, exposing open water. At the same time, a complex system of currents mix cold fresh Arctic water from the north with warmer salty water from the south, as well as fresh meltwater from Greenland’s glaciers. As the water mixes, it forms layers, and nutrient-rich water is pushed to the surface in what is called an “upwelling.” When the sun’s rays penetrate the surface of the polynya, the light creates the perfect environment for phytoplankton blooms, which are the basis of the food web for all other marine creatures.

“It’s such a biological hot spot and attracts so many animals to the polynya,” Dahl explained. “Inuit communities rely on that wildlife for subsistence hunting.”

But communities in both Nunavut and Greenland are concerned about the environmental risks of increased commercial ship traffic through the polynya related to industrial development such as mining, Dahl said. “We are concerned that more ships passing through the polynya will disturb the narwhal.”

Climate change is also affecting the polynya and posing new threats. If the ice bridge fails to form, ice floes drift into the polynya, blocking sunlight and reducing the phytoplankton blooms. That has an impact on the entire marine ecosystem of the polynya, she said. This has happened on occasion over the past two decades and could become more frequent as the Arctic warms.

A 2017 report called “People of the Ice Bridge: The Future of the Pikialasorsuaq” was issued by the Pikialasorsuaq Commission and made recommendations for the conservation and management of this region following consultations with communities in both Nunavut and Greenland. Since then, the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) – Canada and ICC – Greenland have worked to promote the implementation of the recommendations and supported regional and national negotiations to develop an Inuit-led management regime.

The project recently hit a major milestone: Canada and Greenland have now signed an agreement to work together towards conserving this important ecosystem, and the steering committee will have Inuit representation from both sides of the polynya. “Research shows that marine protected areas are a simple and effective way to preserve biodiversity in the sea and build resilience,” said Jenseeraq Poulsen, Executive Director of ONKN. At a time when climate change is accelerating with an impact on fisheries and wildlife, Oceans North Kalaallit Nunaat is in favour of protecting Pikialasorsuaq through a management regime that supports Inuit visions for an effective seascape.”

To learn more about Pikialasorsuaq, visit Oceans North Kalaallit Nunaat’s website.

Ruth Teichroeb is a regular contributor to Oceans North and is former communications director. She lives in Sidney, B.C.