Managing Fisheries in an Age of Climate Change: American Lobster

This blog is part of a series on how to incorporate climate change into fisheries management. Click here to learn more and read an introduction to the project, or check out our other case studies on Atlantic mackerel and Northern Gulf cod.

American lobster have been harvested in Atlantic Canada for centuries. Before the commercial lobster fishery, First Nations harvested lobster for food using spears and traps, and while swimming and diving. Today, lobster (“jakejk” in the Mi’kmaq language) is harvested by First Nations as part of the Food, Social, and Ceremonial (FSC) fishery. The commercial lobster fishery started operating in the mid-eighteenth century following colonization.

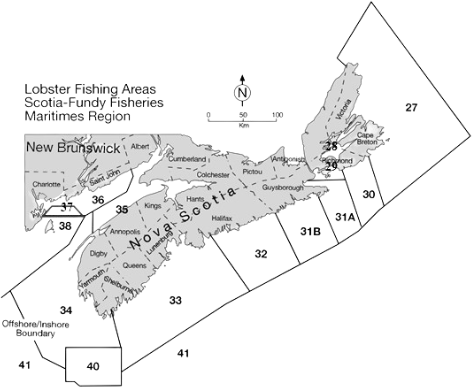

Today, commercial fisheries for American lobster support the livelihoods of thousands of harvesters and coastal communities. It’s also Canada’s most lucrative fishery. Lobster exports reached $3.2 billion in 2021; along the coast of Nova Scotia and the Bay of Fundy, the value of harvested lobster was $898 million. American lobster are fished commercially in Lobster Fishing Areas (LFAs) with baited traps or pots. The fishing season depends on the area, with most fishing occurring between November and May or in the summer months.

A map of Lobster Fishing Areas in the Maritimes Region. Source: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/ifmp-gmp/maritimes/2019/inshore-lobster-eng.html#toc1

Credit: Fisheries and Oceans Canada

American lobster can be found in coastal waters from southern Labrador to Maryland, with the major fisheries occurring in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Gulf of Maine. Lobsters are a temperate species, meaning they require moderately warm temperatures to grow and reproduce. Lobster larvae prefer water temperatures between 10-12°C so they can successfully develop and move from the surface waters to the sea floor, where they settle as juveniles. Adult lobsters can exist in temperatures from 0-25°C and migrate from shallower waters in the summer to deeper waters in the winter. These migrations are thought to take place to optimize temperature exposure for lobsters and their eggs.

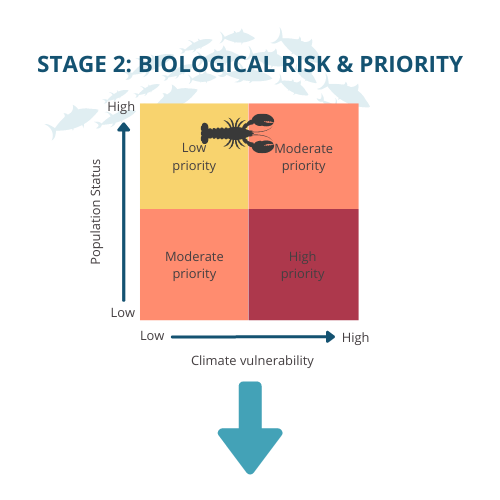

Under the CRIB framework, lobster in LFAs 27-33 are at moderate to high climate risk. These lobster stocks possess higher climate exposure (the degree to which the stock is exposed), relatively low levels of sensitivity (the degree to which the stock can be harmed), and lower adaptability (the degree to which the stock can adapt). Lobster found in LFAs 35-38 and LFA 41 are at a moderate climate risk.

These lobster stocks are currently at healthy levels. Healthy lobster populations are more resilient to climate change; however, if populations were to decline out of the healthy zone, they would be at a higher climate risk.

Overall, based on the CRIB analysis and the population status, we are putting lobster currently at low to moderate priority based on biological risk.

However, the lobster fishery is faced with new and complex challenges. Lobsters have been moving north from New England into Canadian waters due to changing water temperatures and marine heatwaves. This distribution shift resulted in a 78 percent decline in lobster abundance in southern New England between 1985-2014, and a 515 percent increase in the Gulf of Maine between 1995-2014. While these effects currently benefit Nova Scotia’s lobster fishery, there is no telling if or when the same environmental pressures may cause lobster to migrate even further north, causing the lobster populations in the Maritimes to decline. Additionally, warmer waters could expose lobsters to a variety of problems such as disease, more frequent shell moulting, and reduced fecundity and food availability.

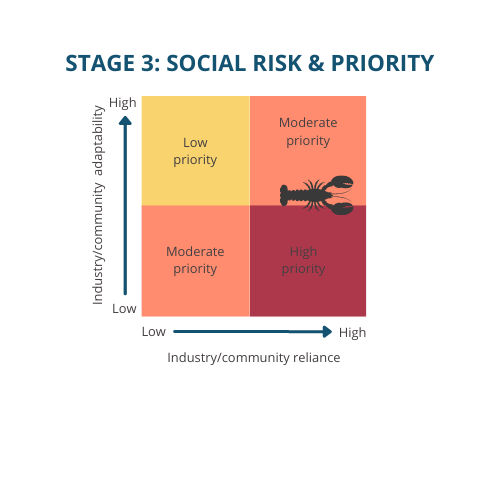

Fishing communities in the southwest of Nova Scotia have a high reliance on the lobster fishery and are extremely sensitive to changes in the abundance and distribution of lobster. High sensitivity within the fishing community decreases the financial resiliency of an area, which therefore increases the social risk. To decrease the social risk of the lobster fishery to communities, managers and the industry must look at ways to both mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Reducing and phasing out emissions from Nova Scotia’s own lobster fishery is one way to mitigate the effects of climate change. Fisheries targeting crustaceans are some of the least energy efficient due to high fuel use. However, zero-emission solutions for marine vessels are evolving rapidly, and the Nova Scotia inshore lobster fleet is particularly well suited to testing and deploying them due to the consistency of operations the proximity of the fishing grounds.

Adaptation strategies will have to account for changes in lobster distribution. These could include licensing and quota adjustments, as well as encouraging harvesters to diversify and fish other target species or obtain non-fisheries related income. Fishery managers should anticipate and adapt to changes quickly to prevent a lag in licensing or quota constraints.

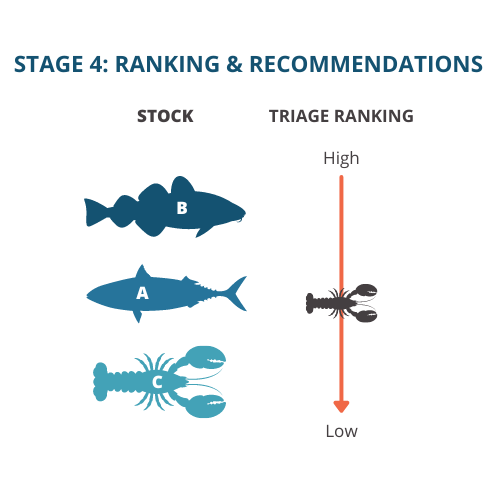

Considering the socio-economic factors in the commercial fishery, lobsters are at a moderate to high social risk based on the extent to which economic reliance on the stocks. However, given the potential of the industry to adapt and mitigate the effects of climate change, we rank lobster at a moderate climate risk.

Overall, we have ranked American lobster at a moderate priority for climate adaptation based on biological and social factors.

If lobster populations shift towards the northeast areas of the Maritimes, they will become less abundant in the southwest. This will mean that areas that rely on lobster as a food and economic resource will have to develop and implement adaptation planning strategies to deal with any changes in potential catch.

However, there is still time to mitigate and reverse climate change effects on the lobster fishery. Mitigation efforts are essential in ensuring the longevity and prosperity of the commercial fishery. While this must occur at the global level, efforts should also focus on the fishing industry. As Canada has committed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 across the whole of its economy, integrating zero-emission technologies into the inshore lobster fleet would be a step in the right direction.

Additionally, research into alternative baits should be prioritized to decrease the reliance on forage fish such as mackerel and herring, whose stocks are in critical conditions. Alternative baits can reduce the overall carbon footprint of the commercial fishery by making it more sustainable, resulting in less waste and less pressure on other fisheries.

Gemma Rayner is Oceans North’s Fisheries and Special Projects Advisor.