How Indigenous Knowledge Helped Identify Walrus Haulouts in Northern Hudson Bay

Credit: Lenny Emiktaut

Despite the Atlantic walrus’ huge size, pungent smell and seemingly lethargic character, information on where they hang out—or haulout—has remained elusive.

Atlantic walrus are big: Bigger-than-a-polar-bear big. A fully grown male can weigh 2,500 lbs, or perhaps even more. These Arctic pinnipeds (a taxonomic group that also includes seals) depend on both marine and terrestrial spaces to live, but how long they spend in the water versus on land isn’t well known. Neither are their migration routes or calving locations. We don’t even know their population size.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that scientists are still unsure about where many walrus haulouts are and whether they’re still in use or abandoned.

Yet while the scientific world has lacked this information, it is available elsewhere. The status and locations of the majority of walrus haulouts are common knowledge for Elders and hunters in Salliq (Coral Harbour) on Nunavut’s Southampton Island, where Oceans North has been working for several years. While there are many ways to learn about walrus, including using technology such as satellite imagery, drones, trail cameras and hydrophones, sometimes the best approach is just to talk to people.

“Walruses are a difficult animal to study, and scientific information on the recent status of many walrus haulouts is lacking,” says Jeff Higdon, a marine mammal biologist who was commissioned by Oceans North and the community of Coral Harbour to author a new report on Hudson Bay walrus. “Inuit hunters have extensive knowledge however, including on the location and status of terrestrial haulout sites, and compiling this knowledge is an important step in improving our shared understanding of this species in the Canadian Arctic.”

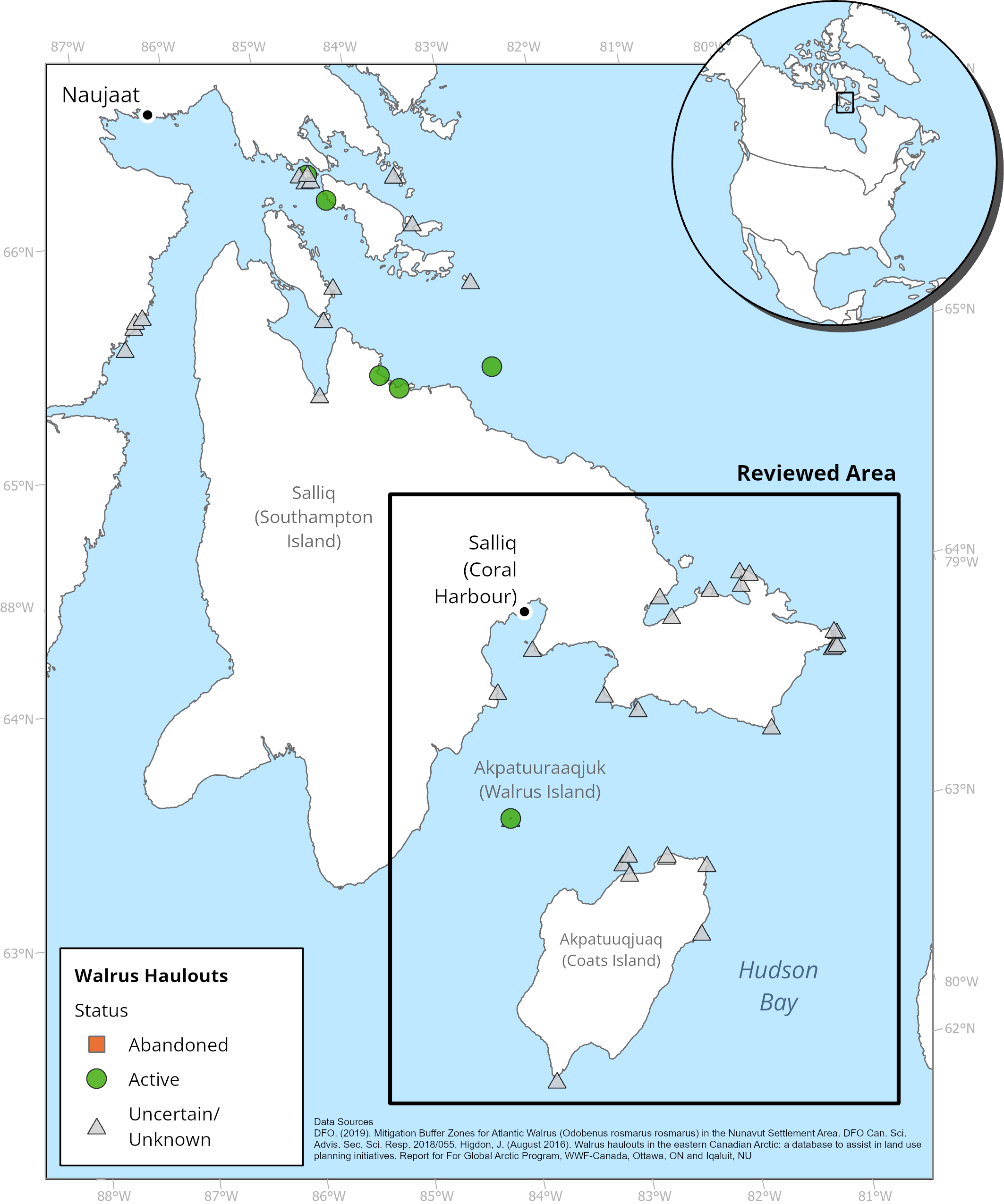

In a recent report on the Hudson Bay-Davis Strait walrus population based on published papers, journals and reports, the best available walrus haulout map was incomplete, especially around Salliq. If you zoom in on Salliq—a place where the surrounding waters are under consideration for a future marine protected area (MPA)—nearly all the haulouts for walrus are listed as “unknown” status.

To address this information gap, we printed the best available map and started knocking on doors to see what Coral Harbour residents thought. Leonard Netser, an Oceans North contractor and renowned walrus hunter, visited Elders, spoke with fellow hunters and worked with the Aiviit Hunters and Trappers Organization (HTO) to gather more information on haulouts around the island. They talked about walrus locations, abundance, whether they had seen them in the past, or recently, and differentiated whether the areas were official haulouts or just places that walrus were sometimes seen. Elders could make this distinction based on their deep understanding of the land and the species. According to Leonard, another reason it was important to ask elders is that some haulouts further from the community may have never been visited by current hunters, especially if those sites are now abandoned.

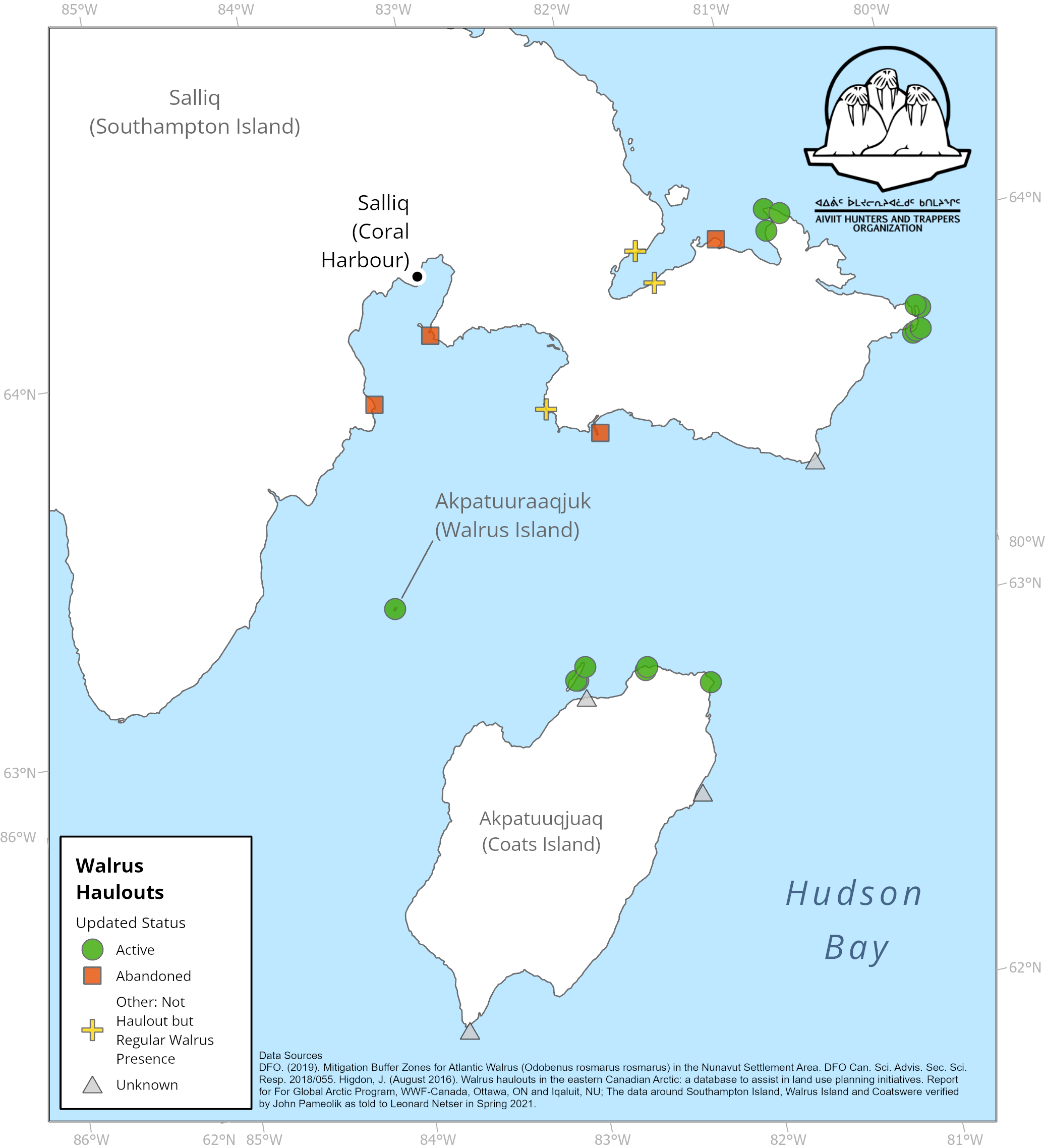

After speaking with walrus experts, the status of nearly all the “unknown” haulouts near the community had been updated to reflect whether they were “active” or “abandoned.” One elder in particular, John Pameolik, provided a wealth of knowledge to update the maps, and he also communicated his expertise through stories about walrus behaviour, preferences and haulout abandonment.

Figure 1: Best available walrus haulout map before community interviews.

Figure 2: Updated walrus haulout map after community interviews, Aiviit HTO. 2022

It turns out that walrus are very picky when choosing haulouts because they require specific things, including: rocks that are easy to climb to get in and out of the water; strong currents to churn up bottom sediment (which helps walruses collect clams, one of their main food sources); locations close to a shallow feeding area; and a healthy benthic environment.

Walrus also have very sensitive hearing and communicate using a wide array of clicks, clacks and whistles, so a quiet area is likely preferred as well. In short, these marine mammals have very niche ecosystem habitat requirements.

Some haulouts are thought to be thousands of years old and have been used by generations of walrus. This makes sense given all of the components that are needed to form an ideal haulout. Once walrus find an area that meets all their needs, they tend to use it year after year, decade after decade. However, if there is a significant disturbance, like a walrus being killed at a haulout, or repeat disturbances (which can cause stampedes), a haulout may be abandoned forever.

“Walruses are known to abandon haulouts when too much hunting pressure is exerted on the haulout itself,” said Leonard Netser. “One known example of abandoned haulouts is around the north of Chesterfield Inlet, where RCMP killed a whole colony of walruses on an ugli (or haulout) for ivory and dog food. Undoubtedly some animals escaped the slaughter but the ugli has never been used again in roughly the last century.”

While identifying and labelling haulouts may not seem like a major accomplishment (especially since the community always knew where they were), it is an important step in ensuring that both science and traditional knowledge contribute to a broader understanding of complex marine ecosystems. In this case, having a more robust information base from a variety of sources allowed us to update an incomplete haulout map that will be used for many applications. The new map, published by the Aiviit HTO, can help inform community guidelines, vessel and transportation advice, conservation initiatives, and various marine policy, regulation, and management decisions.

Incorporating many types of knowledge systems can be complicated and messy, but the resulting product is more comprehensive and accurate, creating a better picture of our natural world and the many species that call it home—including walrus.

With the status of several haulouts still uncertain to the north of Salliq, Oceans North plans to work with the community of Naujaat in the near future to complete the regional map.

To learn more, check out our first edition of The Walrus News, our blog, or the Northern Hudson Bay walrus report.

Colleen Turlo is a policy advisor at Oceans North and is based in Halifax.