Why Age Is More Than Just a Number for Atlantic Mackerel

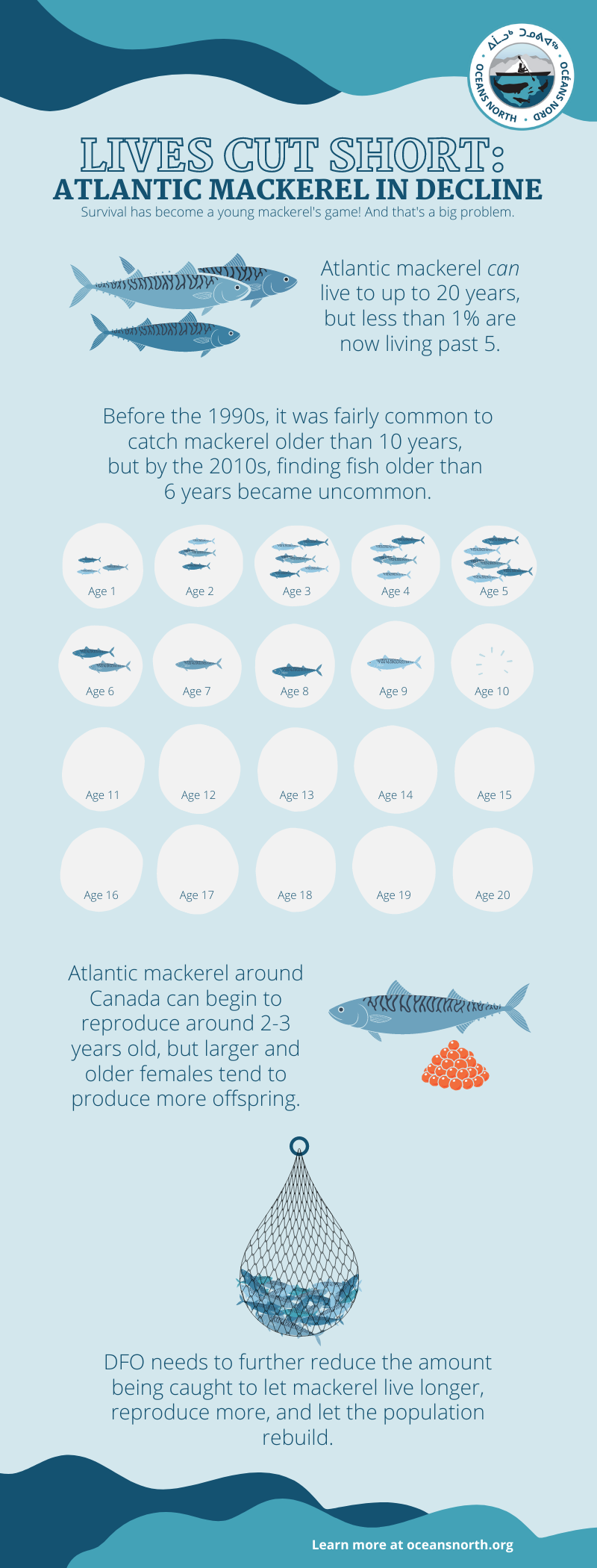

But something less well known is that we are also witnessing the collapse of the mackerel stock age structure. What does that mean? While mackerel can live up to 20 years, we rarely see fish more than five years old now. In fact, less than 1 percent of remaining mackerel are older than five. Unfortunately, this is a common feature of overfishing: over many years, the fish that are caught get smaller and smaller, which roughly translates into a declining age structure. Before the 1990s, it was common to catch a mackerel older than 10 years.

This has huge consequences for the mackerel population’s ability to rebuild. In the world of fish, larger females are more fecund, meaning they can produce more and higher-quality eggs that go on to make more mackerel. So with only small, younger fish left in addition to the low numbers overall, it’s a big problem.

While quotas have been decreasing in the last decade, the actions taken have largely been too little, too late. The stock has very little chance of increasing back to healthier levels under current conditions.

However, the effect that fishing has on the mackerel population remains significant—which means that reducing fishing to the lowest possible levels offers a good chance of rebuilding the stock. And when they do come back, we need to make sure some of these fish reach a ripe old age.

To learn more about Atlantic mackerel, listen to the first episode of The Ocean Project, a new podcast from Oceans North.

Katie Schleit is a senior fisheries advisor at Oceans North.