Claws of Attraction: What’s the Perfect Lobster Bait?

Student researchers drop a tripod with a camera and bait bag into the ocean.

Credit: Katie Schleit / Oceans North

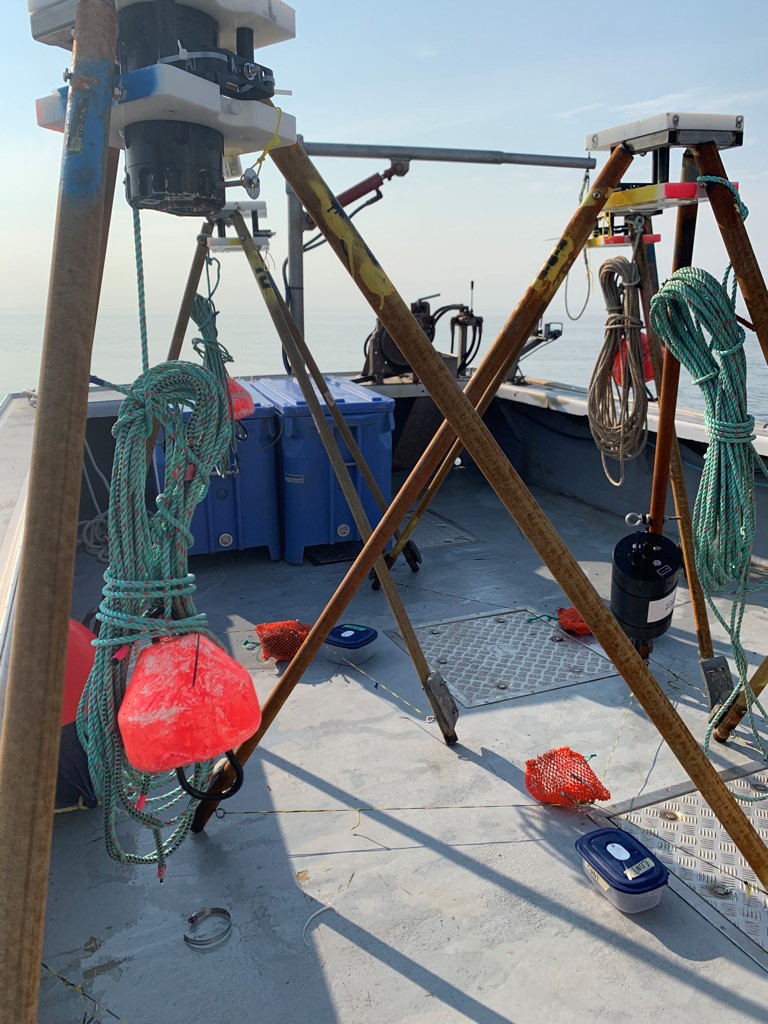

Tripod, bait and camera systems awaiting deployment.

Credit: Katie Schleit / Oceans North

The theory and technique of lobster fishing has remained mostly unchanged for a long time: you put bait in a trap, you wait for the lobster to go into the trap, and then you pull the trap up.

There hasn’t been much science done on how or why lobsters pick one trap over another. The team from Dr. Russell Wyeth’s laboratory at St. FX is changing that by conducting underwater field video surveys with a camera and bait bag system to test how lobsters respond to both natural food sources, baits, and new alternative options. The camera is affixed on a tripod with a bait bag attached underneath, giving researchers a bird’s-eye view of the dining room. Today’s menu included chicken offal, shrimp and crab carcasses, but they’ve also tried periwinkles, clams, and more, always comparing those against the traditional standard baits of herring or mackerel.

After the summer field season, they analyze the camera footage to see which baits the lobsters are most responsive to. This involves painstaking work recording how many lobsters show up in and around the various baits as well as tallying up the different kinds of aggressive interactions the lobsters undertake to get their claws on a morsel (the tastier the bait, the bigger the fights).

This sped-up video shows lobsters engaging with Northern shrimp byproducts. The heads, carapaces and digestive tract (usually composted during processing) were rolled into cylinders and frozen ahead of the experiment.

Credit: Grace Walls / St. Francis Xavier University

Other elements of the research include looking at the larger scale movement patterns of lobsters relative to bait odour plumes generated by lobster traps: think of a cartoon character inhaling and levitating towards the aroma of a pie resting on a windowsill, but with rotting fish. In the future, they also plan on analyzing the constituents of the different baits for their attractiveness to lobsters, such as naturally occurring oils in baits or the building blocks of proteins. Together, these findings could help industry optimize the placement of traps and develop new bait alternatives, lessening the need to catch vulnerable populations of bait fish.

After we dropped the last of the tripods into the water for the day, we sailed back through the calm seas to the wharf in the haze of late afternoon. During the lobster fishing season, the wharf would be bustling with harvesters and traps but today it was swimmers at the beach and visitors getting ice cream at the lighthouse. Maybe the lobsters were already scrambling towards the tripods to try out some new bait.

Katie Schleit is a senior fisheries advisor at Oceans North.