How Does Ship Traffic Affect Narwhal in Nunavut’s Eclipse Sound?

Narwhals surfacing near Baffin Island, Nunavut.

Crédit : Michael Valos

In 2014, a team from Oceans North placed its first hydrophone in Nunavut’s Milne Inlet to collect acoustic data about narwhal that migrate there from Baffin Bay each summer. At the time, the Mary River iron ore mine was about to open on this inlet at the southern end of Eclipse Sound, bringing with it a significant increase in ship traffic. Residents of nearby Pond Inlet, especially members of the Mittimatalik Hunters and Trappers Association, were concerned about how that traffic might disturb narwhal.

“The goal of our research was to monitor the presence and absence of narwhal, and changes in their behaviour when ships were in the area,” said Kristin Westdal, marine biologist for Oceans North.

Now, preliminary findings from the ongoing study suggest that narwhal could be at risk from the dozens of bulk cargo ships and supply vessels that make more than 150 trips each summer through Milne Inlet from the mine, owned by Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation. The ship traffic could increase to more than 350 trips a year if a company proposal to expand production is approved. And these vessels also travel through the nearby proposed Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area.

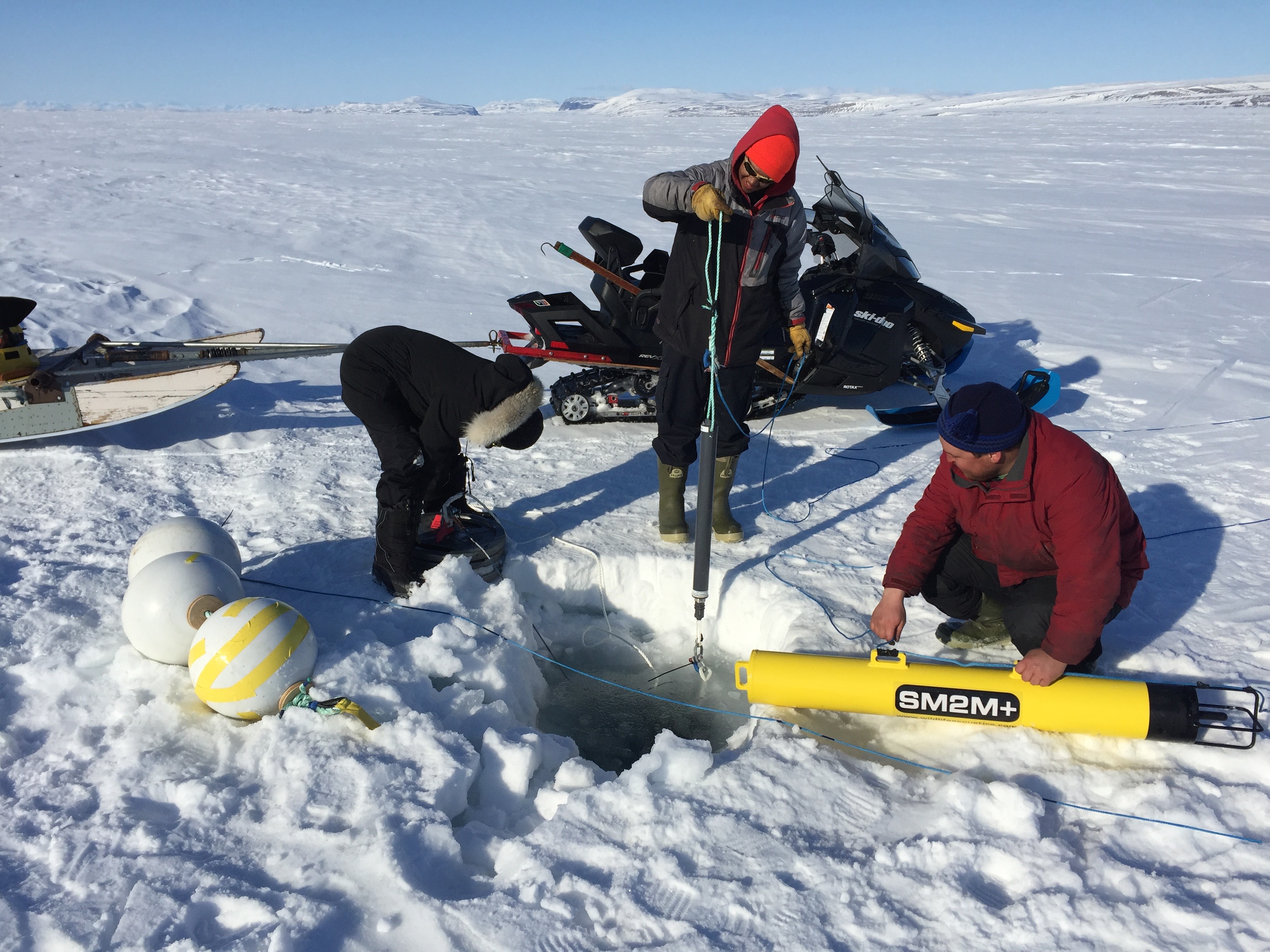

Oceans North team deploys acoustic monitoring device in Milne Inlet.

Crédit : Oceans North

Narwhal are very chatty marine mammals, communicating with buzzes and whistles and producing clicks to find their way around underwater. Their sounds also provide a good way to track them. To establish a baseline comparison for the acoustic monitoring in Milne Inlet, researchers also placed a hydrophone in nearby Tremblay Sound where narwhal don’t encounter large ships.

“We found more hours of calling per day by narwhal in Tremblay Sound than in Milne Inlet,” Westdal said. “There’s more vocalizing in the fjord that has no shipping.”

Westdal and her research partner also discovered that narwhal “burst-pulse” and buzz-type calls used for social communication occur at frequencies that overlap with vessel noise. That could be a problem for narwhal, which use sound to find prey, navigate, and communicate with each other. Repeated daily masking of communication by vessel sounds could have negative impacts on individual, group and the population as a whole over an extended period of time.

Preliminary modelling also suggests that whales summering in this area are at risk of temporary hearing loss due to vessel noise. Permanent hearing loss in specific cases is unlikely, but not out of the question.

Last year, Baffinland’s mine shipped 5.1 million tonnes of ore through Milne Inlet on 71 cargo ships between July and October. The company wants to triple the amount of ore transported out to 12 million tonnes per year and has proposed increasing that up to 30 million tonnes by 2025.

“We’re up against a time crunch to understand what’s happening to narwhal before there’s a further increase in shipping,” Westdal said. “The more information we have, the more we can mitigate the impacts of noise on these whales.”

More research should be done before allowing an increase in mine-related vessel traffic in this region, including mapping cumulative sound exposure levels from different types of ships in four locations along the route.

Scientists from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California joined the study in 2016 and provided two sophisticated acoustic devices called High-frequency Acoustic Recording Packages, or HARPs, that can record 24 hours a day throughout the year.

This summer, our research will continue using one seasonal hydrophone and two HARPs. The acoustic devices also record useful data about other marine mammals in the region, including killer whales and more recently sperm whales. With the loss of sea ice, the killer whale population has increased in the Arctic, putting narwhal at greater risk for predation.

As commercial ship traffic increases, it’s more essential than ever to collect data about how vessel noise affects narwhal. Supporting a healthy narwhal population is important to the overall marine ecosystem and the Arctic communities that rely on marine mammals as a food source.

Ruth Teichroeb is senior manager of communications at Oceans North.