Installing Sea Ice Cams in Nunavut’s Eclipse Sound

The weeks leading up to our trip in early June to install two time-lapse cameras on Mount Herodier above Eclipse Sound were busy and challenging. I had to configure and troubleshoot the camera systems that would transmit images of sea ice conditions before and after spring breakup, and plan for an array of possible equipment failures. My colleague, Patty Chambers, and I had to pack for highly variable Arctic weather, stuffing our oversized duffels.

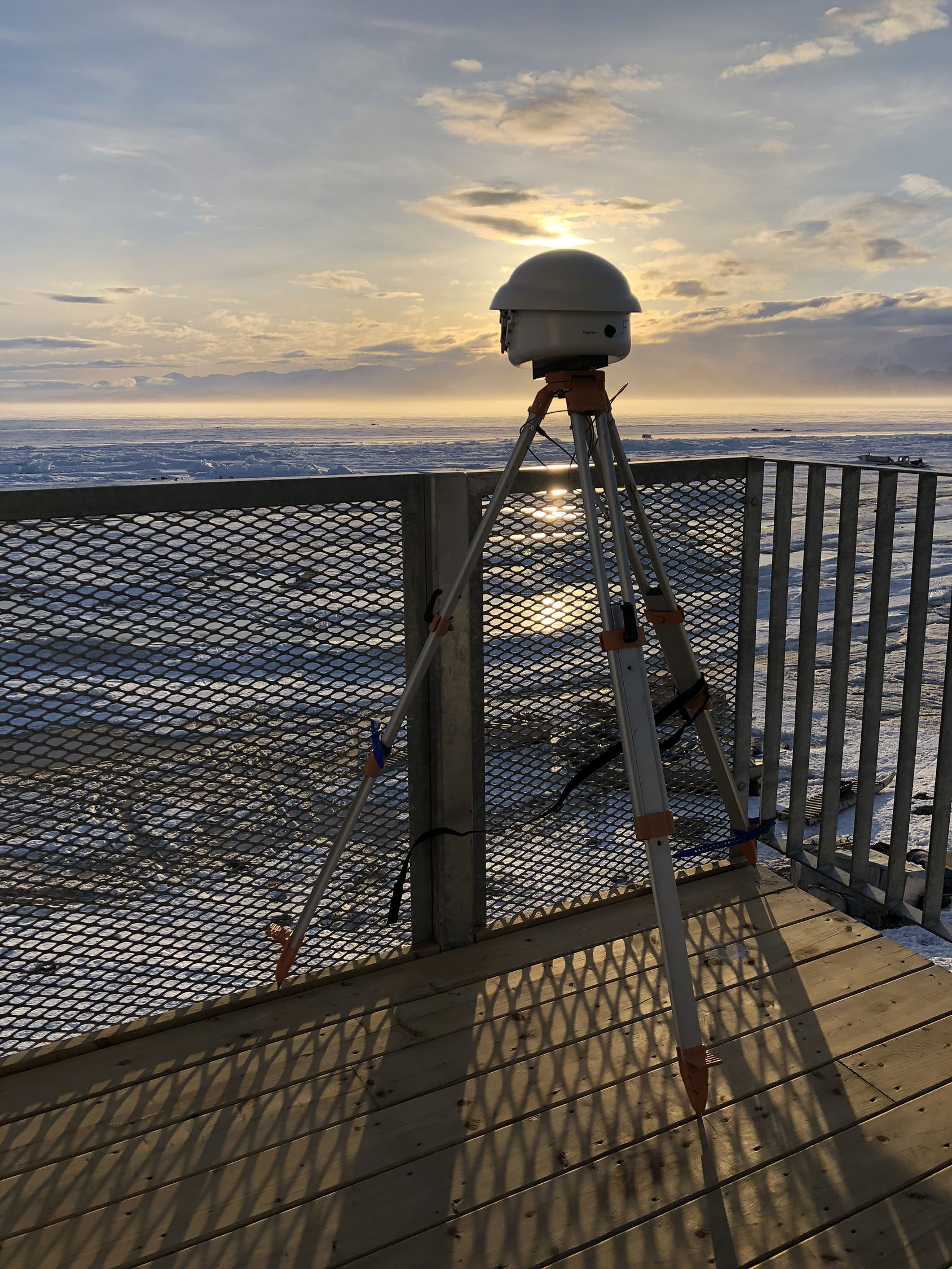

Looking east toward the floe edge, the Floe Cam is one of two time-lapse cameras located on the summit of Mount Herodier, west of Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet).

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Eclipse Sound is at the heart of Tallurutiup Imanga, a proposed national marine conservation area that will protect and maintain this rich marine ecosystem. Oceans North has worked closely with five Inuit communities in support of this national marine park.

Once we arrived in Pond Inlet, windy conditions prevented us from deploying the cameras for the first three days. But fortunately, the weather cooperated on the last day, so Patty and I packed up our field gear and headed out.

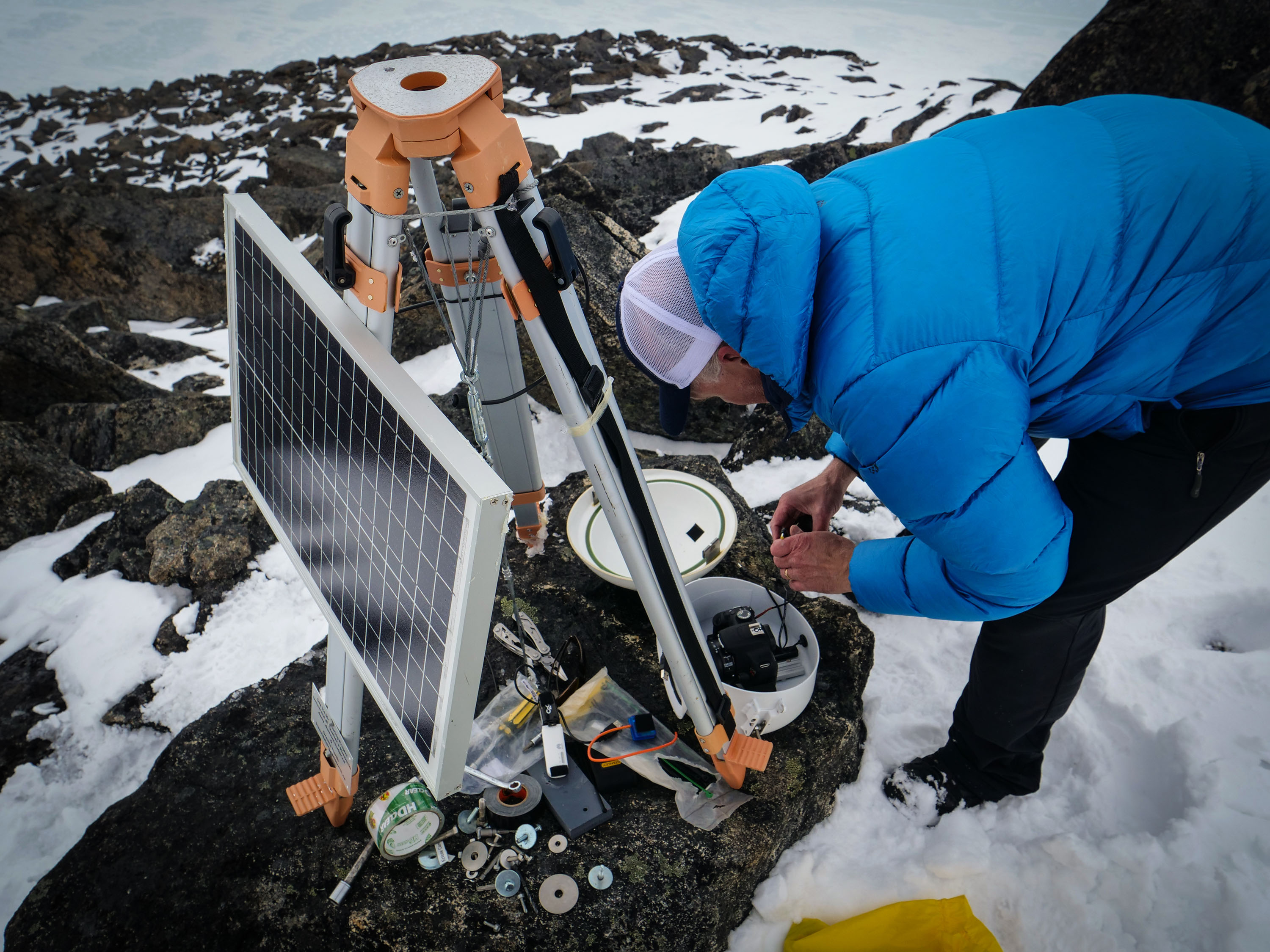

Along with our guides, Alex and Jefferson Ootoowak, we traveled 14 kilometres east to the base of the 675-metre Mount Herodier. There Patty and I donned our heavy packs and started up the challenging three-kilometre hike to the camera site at the summit. At the top, we were able to adjust the two tripods, replace a failing solar panel, and install and test whether the time-lapse camera systems were transmitting to the Oceans North server in the south.

Local guide, Alex Ootoowak, looks toward Mt. Herodier in the distance. Traveling over sea ice requires knowledge and experience of the ever-changing conditions.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

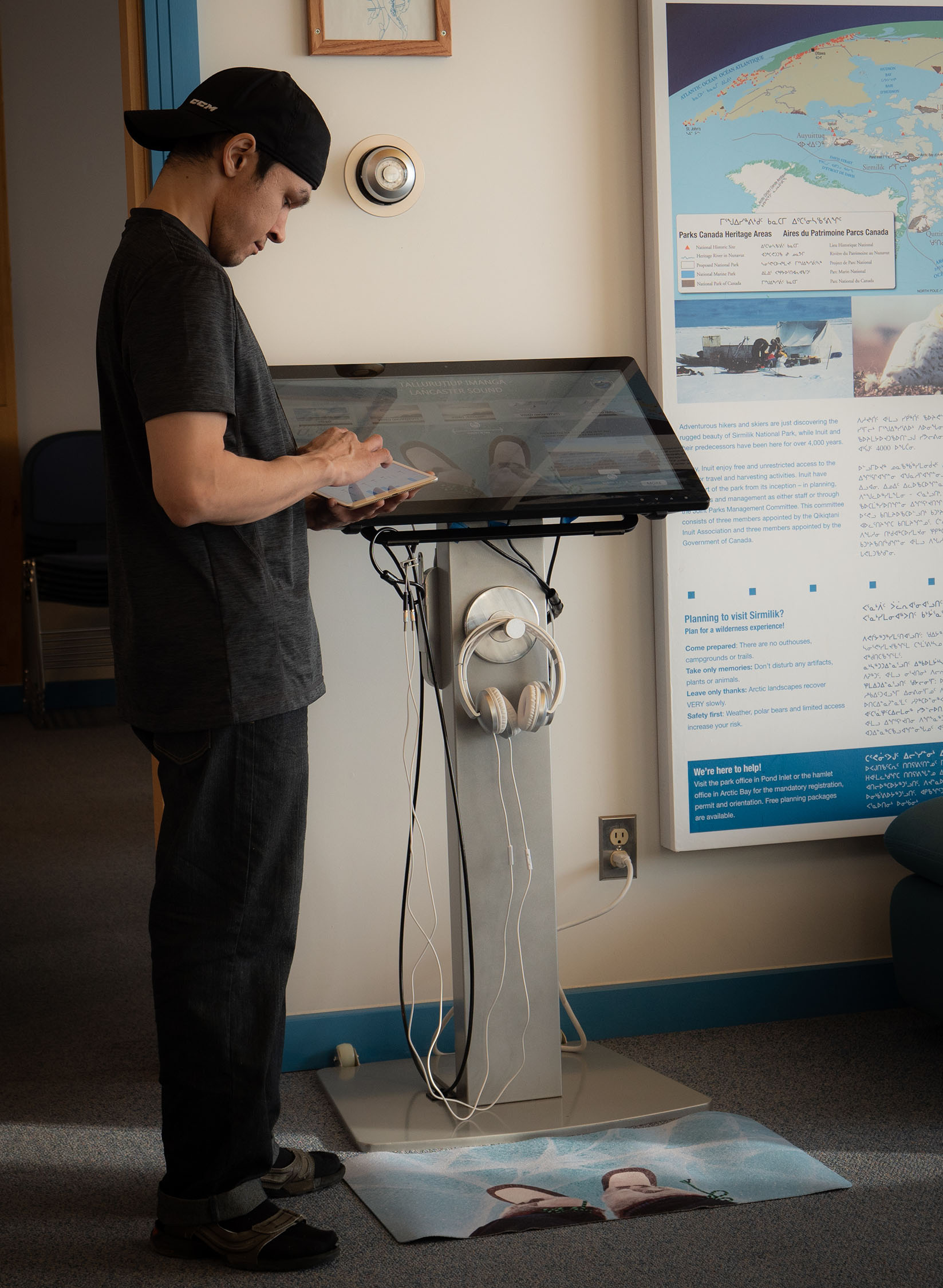

Jeremy Davies checks the time-lapse controller and cellular network settings via Bluetooth to make sure they are configured correctly.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

That’s when this text message came in via satellite from colleagues back in the office: “The first pictures are coming in. The image feeds are working!”

Patty and I cheered loudly as we stood at the summit! As we knew from past experience, the successful capture and transfer of images from such a remote location using these complex camera systems was far from certain, so this was cause for celebration!

Back in Pond Inlet, we monitored the incoming images and felt waves of relief with each successful transfer of a picture. These cameras will provide near real-time images of the ice that serves as a highway for the community of Pond Inlet. The time-lapse photos will be available on our website and via the visually engaging touchscreen that Patty installed in the Nattinak Visitors’ Centre in Pond Inlet.

Pond Inlet's Nattinak Visitors’ Centre welcomes guests from all over the world to view its exhibits about the high Arctic. A touchscreen (at left), sponsored by Oceans North, supplies near real-time footage via the ice cams on Mt. Herodier, as well as other videos and community outreach tools.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

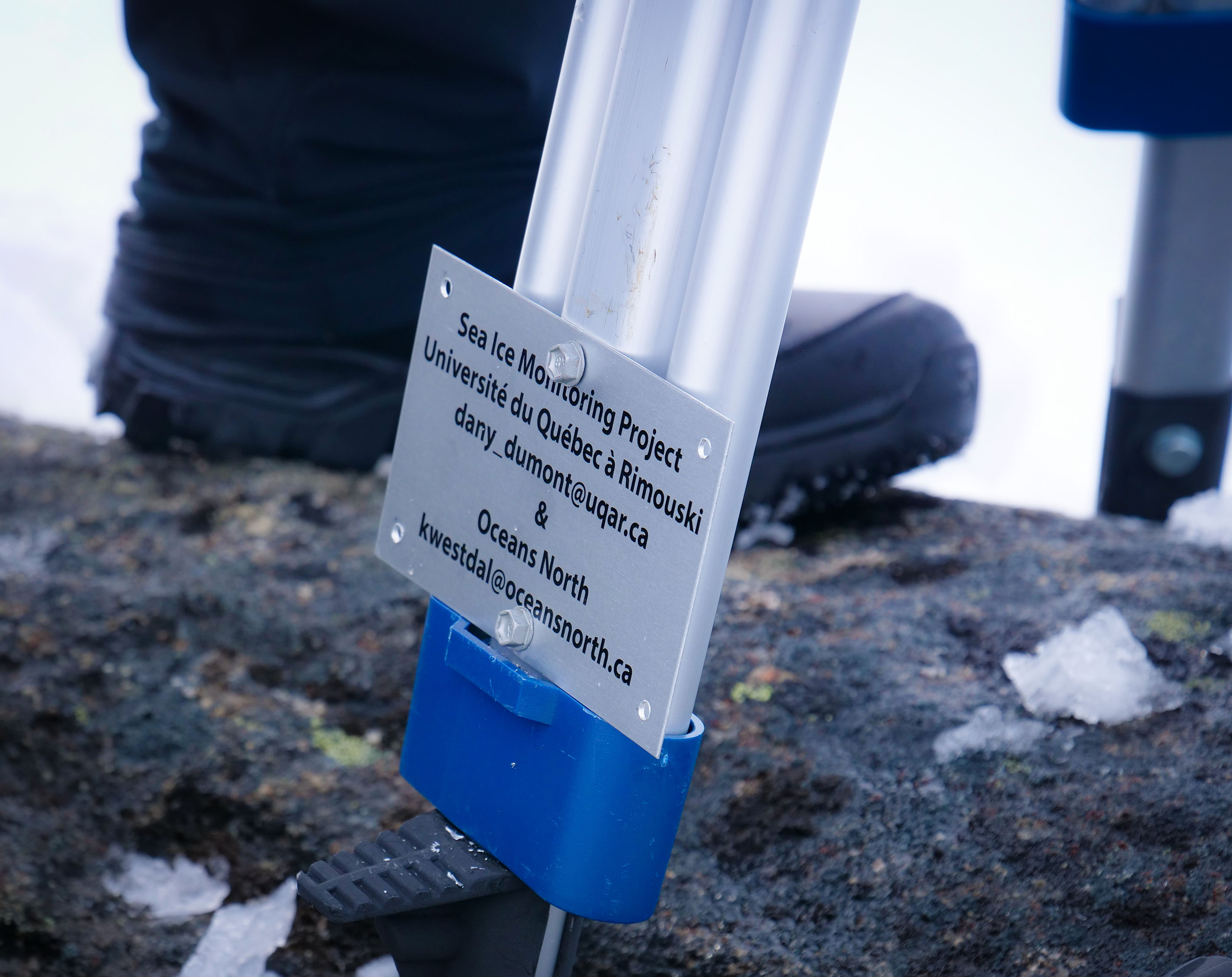

Since 2015, Oceans North has collaborated with Dr. Dany Dumont, of the Université du Québec à Rimouski, and his team at Institut des sciences de la mer de Rimouski (ISMER), on this sea ice monitoring project. The near real-time image feeds will be used by researchers and Arctic enthusiasts to observe and study both the breakup and freeze up of sea ice in Pond Inlet and Eclipse Sound – barring obscured visibility due to inclement weather. With additional data, our partners at ISMER hope to develop a model to accurately predict ice breakup in the region. The images will also help researchers assess the impacts of commercial shipping and icebreaking on the structure of the region’s landfast ice and the biologically rich floe edge.

As we prepared to leave Pond Inlet, Alex asked if he would be able to see the images, as he planned to go to the floe edge to hunt. The camera feeds might reveal if there was enough open water to make his trip worthwhile, though they are no substitute for the traditional knowledge Inuit hunters have developed for safe travel on the ice. To me, this was validation of the best kind—a real-life and practical use of the sea ice images captured by the two cameras atop Mount Herodier.

Jeremy Davies is a marine conservation geographer with Ocean Conservancy which partners with Oceans North on Arctic projects. Patty Chambers is a digital outreach specialist with Ocean Conservancy.

To help ensure that the installations go smoothly, each camera is set up and tested in advance in Pond Inlet.

Credit: Jeremy Davies

Jeremy Davies tests each step of the image transfer process, making final tweaks to camera settings and troubleshooting network bottlenecks.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

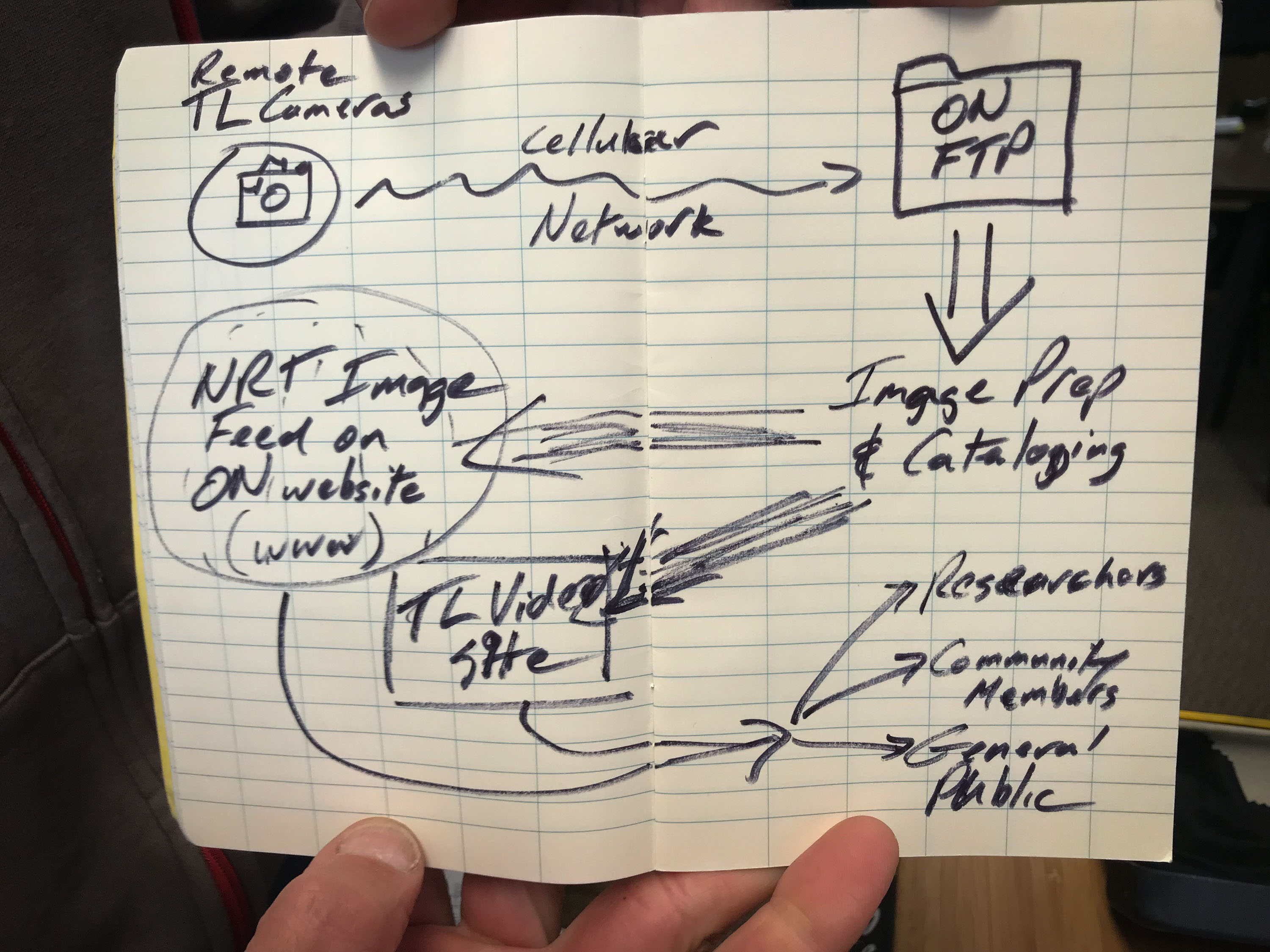

Jeremy’s sketch of a flow diagram tracks how the still images and time-lapse video get from the cameras on the summit of Mt. Herodier to the Oceans North website and touchscreen in Pond Inlet.

Credit: Jeremy Davies

Local guides, Alex Ootoowak (right snowmobile) and his son Jefferson (left snowmobile), survey the scene at the base of Mt. Herodier, picking out a path between jagged rocks, tundra and patches of snow to drive Jeremy and Patty as far up as possible.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Carrying the equipment, “Team Jeremy and Patty” are set to hike up and deploy the ice cams on Mt. Herodier.

Credit: Alex Ottoowak

One foot after the other, the trek to the summit is sure and steady.

Credit: Jeremy Davies

The terrain on hike up the mountain is a mix of snow, ice and uneven rock.

Credit: Jeremy Davies

A silhouetted speck in the distance, Jeremy arrives on the summit. The final precarious approach up the rocky ledge is rewarded with breathtaking views of Eclipse Sound.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Each piece of hardware used to install the camera systems is critical, and Jeremy and Patty work together to make sure nothing is lost during deployment.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Newly installed name plates are added to the cameras’ tripods to provide context and contact information for inquisitive hikers who reach the summit.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

A close-up of newly installed name plates added to the cameras’ tripods.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Jeremy looks through the camera’s viewfinder to check its orientation and field of view.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Team Jeremy and Patty celebrate the successful deployment of the cameras by stepping out on a rocky ledge beneath the Floe Cam for a “Timelapse Selfie.”

Credit: FloeCam/Oceans North

After hiking back to the base of Mt. Herodier, the team returns to Pond Inlet, with Jeremy in tow on a boat lashed to a qamutik and Patty behind Alex on the snowmobile.

Credit: Jeremy Davies

The near real-time footage from the ice cams is fed to the touchscreen at the Nattinak Visitors’ Centre. The Centre’s exhibit manager, Ernest Merkosak, tests network settings and works with Oceans North to maintain the touchscreen.

Credit: Patricia Chambers

Mt. Herodier looms large over Pond Inlet and this team of sled dogs. The time-lapse cameras on Mt. Herodier will provide useful information for local residents who rely on sea-ice travel.

Credit: Patricia Chambers