Connecting to Each Other and the Land on the Indigenous Quest for the Bay

This trip followed in the footsteps of the Hudson Bay Quest Sled Dog Race, the Quest for the Bay documentary television series, and a previous snowmobile tour organized by Heartland Travel and guided by North Star Tours, who guided this iteration.

Credit: Aaron Janzen

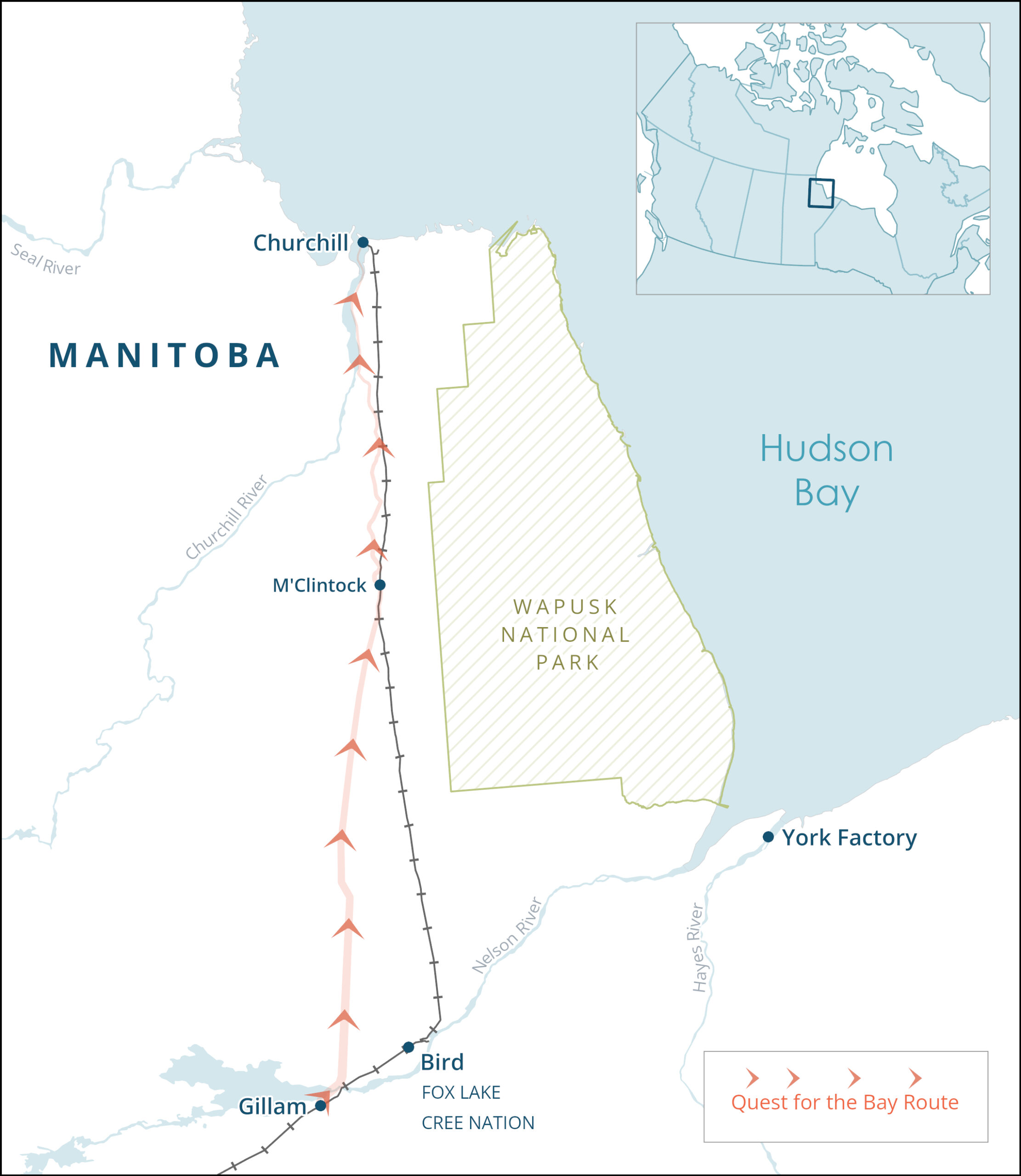

Most people planning a trip to Churchill, Manitoba in March will decide between a slow, scenic train ride or a fast (and expensive!) flight. But there is another way to get to Churchill that is equal parts challenging and rewarding: by snowmobiling 333 kilometres from Gillam.

In early March, despite possessing no experience riding snowmachines, I was fortunate to accompany a group of nine Indigenous women (and their support team) on the inaugural Indigenous Quest for the Bay. This event was envisioned, organized, and led by Heather Spence-Botelho, an off-reserve Fox Lake Cree Nation member and Knowledge Weaver living in Churchill. Heather envisioned the Indigenous Quest, which followed in the footsteps of other events such as the Hudson Bay Quest Sled Dog Race, as a response to the way colonization has altered gender roles in Indigenous communities and disconnected Indigenous peoples from each other, the land, and traditional teachings. Heather’s goal was twofold: “to connect, build, and strengthen relations amongst our regional Indigenous members and communities” and “to reconnect back to the land in a safe way to feed our blood memory and heal, strengthen, and empower ourselves, together.”

Churchill and the western Hudson Bay region is home to a diverse group of Indigenous Peoples, and the Questers reflected this: there were participants from Fox Lake Cree Nation, Sayisi Dene First Nation, York Factory First Nation, Opaskwayak Cree Nation, as well as an Inuit representative.

Heather Spence-Botelho, Indigenous Quest Leader, reaches the floe edge on the Hudson Bay.

Credit: Aaron Janzen

Oceans North supported this initiative by sponsoring some of the participants, and I was travelling alongside to help document the expedition. Like me, most had never gone that distance by snowmobile, and some expressed a few nerves as we gathered in Gillam the night before our journey began. We shared a meal and some tips about safety protocols before resting for the long trip ahead.

Leaving next morning to the sounds of cheering and honking from local supporters, we were immediately confronted with whiteout conditions crossing the Kettle River. Thankfully, the guides were able to navigate the crossing and we reached the hydro transmission line that runs all the way to Churchill, supplying the town with power and connecting it to the rest of Manitoba. We followed the line most of the day through blowing snow that reduced visibility and led to many of us straying from the trail and becoming stuck in deep powder. We relied heavily on two experienced and extremely capable land users, Briden Botelho and Billy Beardy, who were adept at getting stuck snowmobiles back on track and helping us stay calm and focused along the way. Patience was a theme of the trip, as that first day—which was expected to be a 6–8-hour ride—turned into a gruelling 10-hour journey. We arrived well after dark at McClintock, a cabin set along the rail line to Churchill, where we were greeted with warm food and warm accommodation.

The Questers followed a route from Gillam, Manitoba to Churchill.

Credit: Melissa Turner

The blizzard subsided by the next morning and was replaced by clear, bright skies, while we left the deep powder snow conditions behind for hardened snow drifts. We rode the winding Deer River as it made its way to Dog River, and then on to the Churchill River, whose estuary at the mouth of Hudson Bay is an important site for beluga whales, tourism, and shipping. The scenery was spectacular, and without the blowing snow, we were able to spot the tracks of caribou, moose, otters, and fox. We passed the treeline onto the tundra just as we approached town and were greeted by community members who celebrated the Questers with a lit bonfire, fireworks, honking horns, and cheers to mark the accomplishment!

Willow ptarmigans, and their tracks, were seen all along the Quest route.

Credit: Aaron Janzen

After two full days of riding, many of the Questers slept in the next morning. But a few of us mounted back onto our snowmobiles and rode out onto the Bay, in search of the floe edge. We passed important Churchill sites, like the Port of Churchill (which recently announced it is undergoing redevelopment to ship minerals that arrive via the rail line), and the historic Prince of Wales Fort, built by the Hudson Bay Company to protect their fur-trading interests. Eventually we reached the floe edge, where the sea ice ended and open water appeared. That evening a sweat (Matootsan) was arranged by the Churchill Health Centre for the Quest ladies and women from the town. Heather described it as a “very special way to end the Quest.”

While the long, challenging trip to Churchill reinforced the vast distance between it and many other communities, it also enabled me to see how Churchill is connected in so many ways. Natural and constructed links, such as the rail line, transmission line, animal tracks, and rivers led us to Churchill, while the port and the Prince of Wales Fort pointed to historic and future economic ties to the wider world.

Questers reach the Port of Churchill.

Credit: Aaron Janzen

The importance of intangible connections such as culture, familial bonds, interpersonal relationships, and traditional teachings was also clear. These were what motivated Heather to organize the trip and were made visible through the way the group pulled together to safely and successfully complete the Quest, as well as the community celebrations that marked that success.

Churchill stands at a nexus point, and seeing, understanding, and strengthening (or re-establishing) many of these important connections will be essential as Churchill—and the people, animals, and vegetation that reside there—navigate a changing world.

The Quest for the Bay reached Churchill in the midst of the Aurora Borealis tourist season.

Credit: Aaron Janzen

In the face of these changes, it’s more important than ever that the people who live here have the chance to nurture their connections to the land and sea and have a say in its future. Initiatives like the Indigenous Quest for the Bay, which is to be an annual event, can help strengthen the links between individuals, families, communities, and the Hudson Bay coastline. Another unique opportunity to nourish these vital connections is through the proposed National Marine Conservation Area in Western Hudson Bay. The planning process offers Indigenous and local community members a platform to help lead the ongoing stewardship of these connections in Churchill and along the Western Hudson Bay coast.

Whatever the future holds, I hope to continue seeing and building connections with the people, places, land, water, and animals in and around Churchill—whether I get there by plane, train or even snowmobile.

It is with great sadness that we acknowledge Billy Beardy, a critical member of the Quest for the Bay group, who passed away unexpectedly shortly after the completion of the Quest. Here he is photographed with his wife Tamara.

Credit: Aaron Janzen

Aaron Janzen is Senior Field Campaigner at Oceans North.