Protecting the Deep Sea Before We’re in Too Deep

This tiny dumbo octopus, whose body measured about five centimeters across, was spotted swimming along a seamount at a depth of 825 metres.

ᐃᓕᓴᕆᔭᐅᔪᖅ: NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program

Two thousand six hundred metres below the surface of the ocean it is pitch black: not even a glimmer of light reaches these depths. Yet the gloom is hot—really hot—reaching 400°C. This is a deep-sea hydrothermal vent, one of the most extreme ecosystems on the planet.

Despite being inhospitable for human life, hydrothermal vents are home to a diverse network of organisms. One of these is the yeti crab and they are part of a vibrant deepwater community. Like us, yeti crabs live in unique neighbourhoods that rely on nutrient-rich ecosystems; like us, they have a vocation (in their case, farming chemosynthetic bacteria on their claws); and like us, their ancestors can be traced back to a hydrothermal vent. Scientists believe all life on earth may have originated at hydrothermal vents, connecting all of us to the deep sea, whether you are a human or a yeti crab.

The deep sea harbours some of the least understood ecosystems on the planet: abyssal plains, hydrothermal vents, and seamounts. They are home to a plethora of species—both newly reported and undiscovered—and play a critical role in the ocean life cycle. Many coral, invertebrates (like the yeti crab), octopus (such as the dumbo octopus that lays its eggs on nodules found across the abyssal plains), fish, and whale species (such as the beaked whale that dives to depths over 3,300 metres) live in or travel through the deep sea. Although these species survive seemingly impossible circumstances, they are slow to grow and long lived, making them vulnerable to rapid changes in their ecosystems. The Greenland shark, for example, can live for over 500 years. These creatures of the extreme are not the only ones who depend on the deep sea; species throughout the water column rely on currents that pull cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep to the surface in a regenerative cycle. Furthermore, the deep seabed is an important carbon sink that helps mitigate climate change.

These deep-sea ecosystems are found throughout the world’s oceans, with many existing in international waters. The deep sea and its seabed extend well beyond each country’s 200 nautical-mile exclusive economic zone into the high seas. These international waters and seabed (commonly referred to as “the Area” in international law) cover 50 percent of the Earth and belong to all humankind.

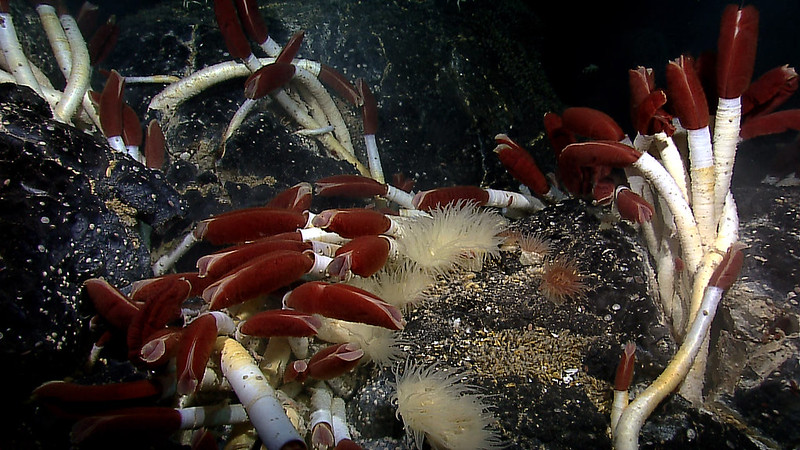

A colony of tubeworms, anemones and mussels found near a hydrothermal vent.

ᐃᓕᓴᕆᔭᐅᔪᖅ: NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program

This vast world, little understood but nevertheless vital to the health of the planet, is in peril. Climate change, pollution, and industry are threatening to destroy the fragile environment and the species that rely on it. Now an emerging industry is putting these ecosystems at even greater risk: abyssal plains, hydrothermal vents, and seamounts are being threatened by deep seabed mining. Metals such as cobalt, manganese, nickel, and copper are found in these ecosystems in high quantities, and are currently used in renewable energy technologies like electric vehicles.

Proponents of deep seabed mining claim the metals sourced from the seabed will facilitate the green energy transition, even though its necessity and sustainability are contentious. Many companies, including Volvo, BMW, Samsung SDI, and Google, have pledged not to source metals from the seabed in favour of more sustainable alternatives. Moreover, recent innovations are creating batteries without cobalt that are better for the environment. When only 20 percent of metals are recycled each year globally, the transition to a green, circular economy cannot be responsibly undertaken by introducing a new extractive industry. Despite the “green” claims made by some of its proponents, the rush to mine the seabed, though lucrative for the corporations involved, is likely to be a disaster for the environment.

Extracting metals from any of the three target ecosystems would result in a net loss of biodiversity. Science shows the effects of deep seabed mining cannot be localized to the mining site, and will instead impact the entire water column and the species therein. Furthermore, the high seas and seabed represent one of our few remaining opportunities to preserve a largely intact ecosystem for future generations. Why destroy the 50 percent of the planet that remains virtually undisturbed by human industry?

Corporations want to start mining in international waters as early as 2023, but they are not yet able to do so because there are no international regulations established to manage deep seabed mining. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is the institution responsible for overseeing the international seabed (the Area), and has yet to finalize regulations for exploitation. The current draft regulations are not robust enough, nor have they seen enough significant international consultation to be approved. Weak regulations pose a catastrophic risk to the seabed and communities who live in close proximity to proposed mining sites. Per the ISA’s mission, it is tasked with managing the Area’s resources for the long term benefit of all humankind. Thus, no industry in the seabed should commence that will not have a positive impact on all states. Many coastal states and communities around the world are unlikely to see any benefits from deep seabed mining; they are already disproportionately affected by climate change, and could face serious impacts to their livelihoods if marine ecosystems are damaged. This ISA process and the exploitation it leads to can be stopped if states such as Canada become leaders and champion environmental stewardship for the equitable benefit of humanity.

Oceans North is committed to protecting the marine environment so it can continue to sustain us and the rest of the planet for generations to come, which is why our organization cannot ignore threats to the international seabed. Oceans North is asking the Government of Canada to join the European Parliament, the European Commission, the UK House of Commons Environment Audit Committee, The Pacific Blue Line, as well as many civil society organizations, faith-based groups, and deep sea scientific experts in their calls for a moratorium on deep seabed mining in international waters.

Deep seabed mining is already effectively banned in Canadian waters under the Fisheries Act, which limits the deleterious substances that can be released in fish habitats in order to protect fish ecosystems. Allowing it to go ahead in the high seas is also inconsistent with our international commitments. Canada is a member of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, which called for a moratorium on deep seabed mining in its Sustainable Ocean Economy report. If Canada will not allow deep seabed mining in its own waters, how can we allow it in our global commons—the international seabed?

If you would like to join the global chorus calling for a moratorium on deep seabed mining, Oceans North is sponsoring a parliamentary petition you can sign that, when enough signatures are reached, will require a response from the Government of Canada.