Finding Sea Creatures and Our Sea Legs in James Bay

The Research Vessel William Kennedy, a retrofitted fishing boat, carried 14 research team members and six crew during the 17-day research expedition to James Bay.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

Around 2 a.m. on August 1, Captain David McIsaac of the Research Vessel (R/V) William Kennedy told us we would be leaving Churchill, Manitoba right away. Heavy winds were coming into Hudson Bay, and we had to get ahead of them if we wanted to get to our destination. The engines of the retrofitted fishing boat started roaring and rumbling—a noise we would get accustomed to very quickly—as we departed on our 17-day research expedition to James Bay.

The purpose of our expedition was to gather data about the physical, chemical and biological oceanography of James Bay, the southernmost extension of the Arctic Ocean. James Bay’s relatively fresh, shallow waters are fed by large rivers, some of which have been dammed for hydroelectricity. This region is home to polar bears, belugas, and large numbers of migratory birds. Nearby Cree communities, who have used the waters and coasts of James Bay for generations, have witnessed changes to the ecosystem over the past decades and asked for more research to be done into the causes. Despite the bay’s large size and ecological importance, scientists know very little about it. The expedition’s research would shed light on how conditions have changed and help predict how this may not only affect traditional practices, biodiversity and environmental processes, but also potentially impact climate on a global scale.

I was the communications and outreach lead among the 14-person research team and six crew members aboard the William Kennedy. Captain McIsaac used to run the boat back when it was a fishing vessel in Prince Edward Island; his chief mate is his son Daniel, and most of the crew is also from PEI. The researchers came from the University of Manitoba, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Université de Sherbrooke (Québec). I flew from Winnipeg to Churchill to meet the William Kennedy at the port. There, we had a final COVID test before we got on board, unpacked the research material (shipped weeks ago by train) and organized the lab. For the few of us who had not yet been to Churchill, we were amazed by the astounding number of belugas in the Nelson River Estuary. We could literally see dozens of whales with one glance!

The weather was rough for the first couple of days of the trip to James Bay. Within hours of leaving, we knew who would be cursed by seasickness (spoiler alert, I was one of them) and who seemed immune to it. The vessel also had very limited space and, with 20 people all living and working together, moving out of people’s way while the swell was rocking us was a dance we got to master very quickly. Cha-cha-cha!

The science operations began on the afternoon of August 3 after we rounded Cape Henrietta and deployed the CTD-rosette, a device that measures the conditions of seawater at different depths (see slideshow below). At midnight, we deployed the first of six moorings, a device that passively collects physical, chemical and biological oceanographic data. The next morning, we arrived at our first full sampling station.

A CTD-rosette sampler is a device fitted with Niskin bottles which can sample water at specific depths and is paired with an instrument used to measure the conductivity (a proxy for salinity), temperature, and pressure (a proxy for depth) of seawater. Here, the rosette is being brought back from the depths by CJ Mundy (Chief Scientist, University of Manitoba) and Elizabeth Kitching (M.Sc. student, University of Manitoba).

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

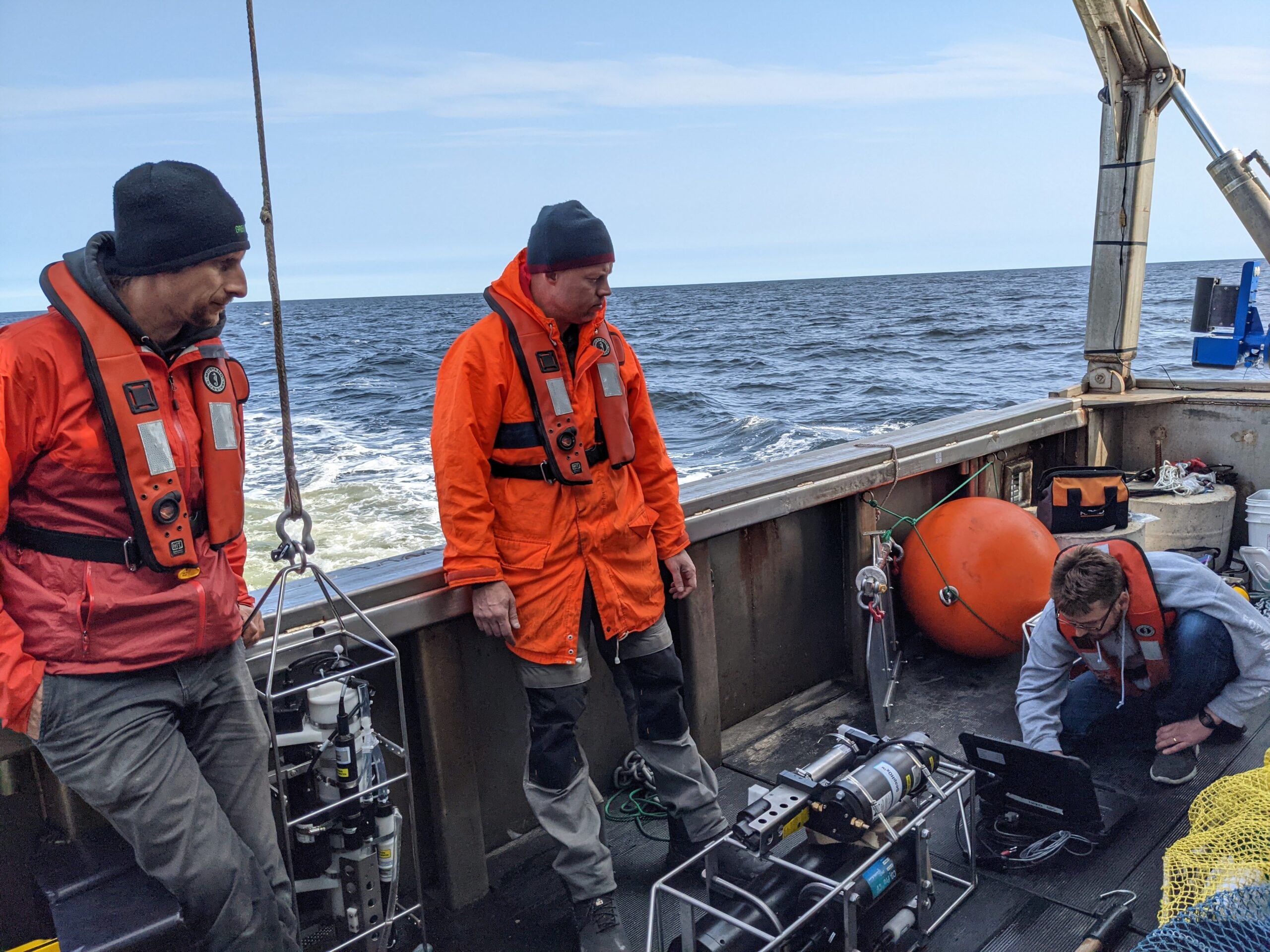

Dylan Hardie and Tyson Arsenault (crew members), Sergei Kirillov (research associate) and Jens Ehn (co-principal investigator) deploy a mooring lined with many instruments that will record data about the oceanography of James Bay over the upcoming year.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

Kate Yezhova (M.Sc. student, University of Manitoba) and Zou Zou Kuzyk (Co-prinicipal Investigator, University of Manitoba) sample and bag a sediment core for further analysis.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

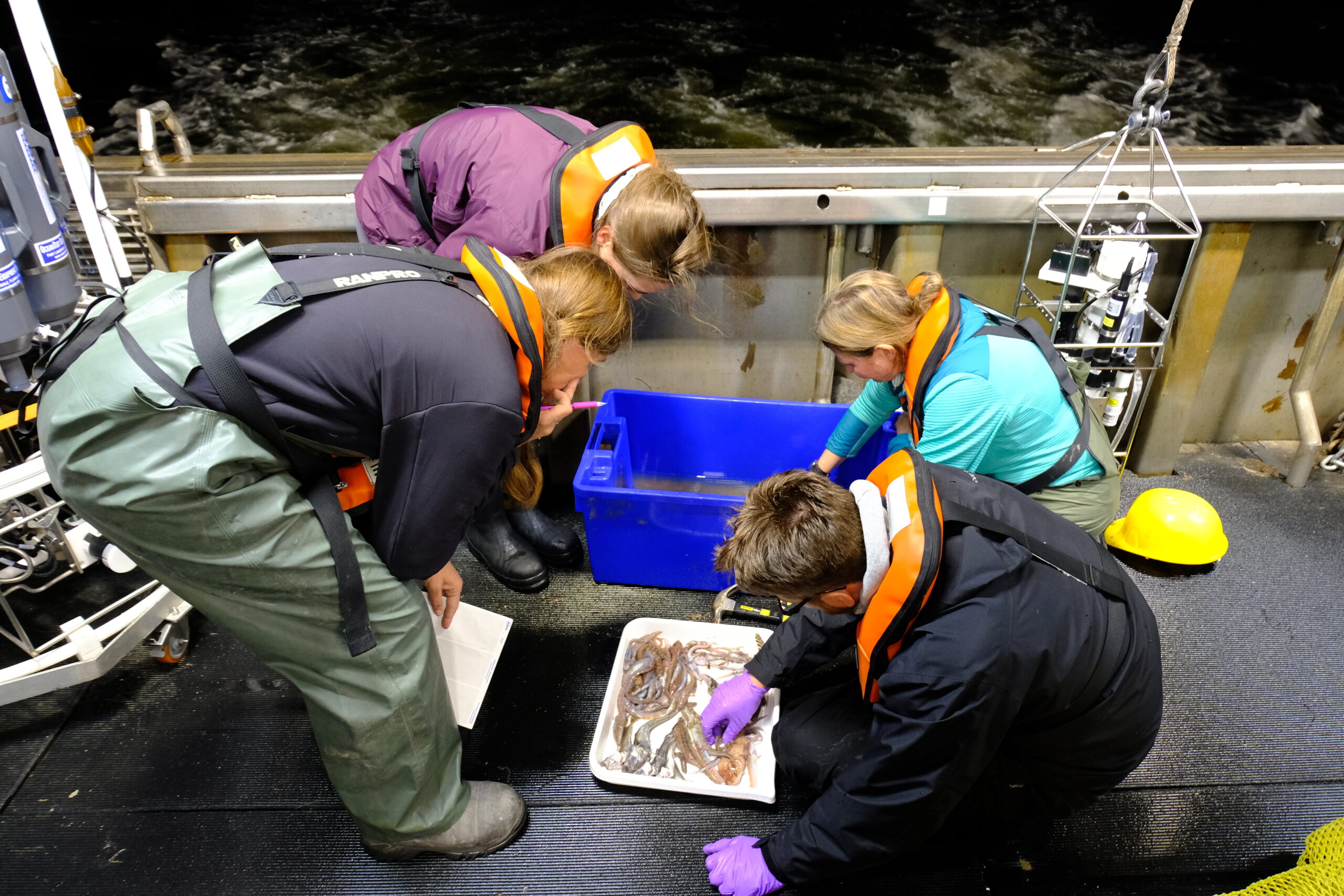

Kimberly Howland (research scientist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada), Janine Hunt (technician, University of Manitoba), David Capelle (physical scientist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada) and Zou Zou sorting the “catch of the day,” i.e. the animals brought up from the depths by the beam trawl net.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

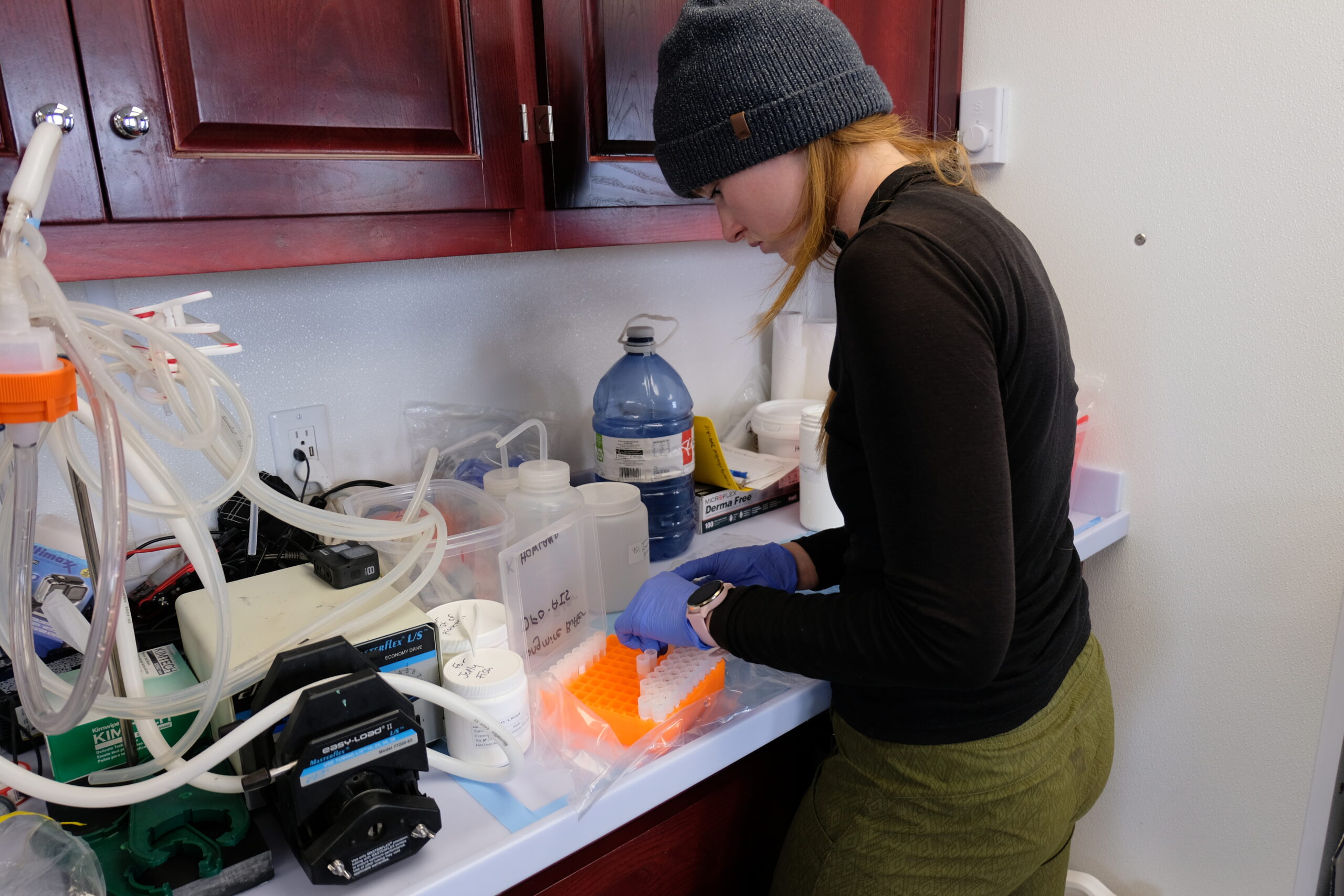

Master's student Lauri Corlett (University of Manitoba) filtering some samples in the lab.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

Master's student Alessia Guzzi (University of Manitoba) filtering some samples in the lab.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

Elizabeth in her green-lit environmental chamber working on some water samples.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

Kimberly Howland (research scientist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada), Jillian Reimer and Alessia Guzzi (master's students at the University of Manitoba), and Dylan Hardie (crew member) depart on the Zodiac for nearshore surveys (environmental DNA, kelp, water sampling, etc). They spent about 10 hours in the zodiac that day.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

Moorings like the one pictured here will stay in the water to collect data until they are retrieved next year.

Ilitariyauyuq: Maude Durand / Oceans North

A typical sampling day involved all kinds of different instruments. First, the rosette would be lowered to sample seawater at different depths under the supervision of technician and wonder woman Janine Hunt. Then sediment from the seafloor would be cored and grabbed for sampling and processing on board. The sediment core would be sliced and bagged by co-principal investigator Zou Zou Kuzyk and master’s student Kate Yezhova from the University of Manitoba. The grabbed sediment would be sieved and the animals living in the mud (often a lot of tiny worms and critters) would be harvested and packed for further analysis by Kim Howland, a researcher with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, with the help of whomever was available (including me when seasickness allowed it). Finally, the beam trawl net (a big net that’s towed over the seafloor) would be set to catch shrimps, sea stars, fishes, crabs and other wondrous animals. Emptying the net was usually a highlight of the day: sorting out the catch was like a treasure hunt.

All the while, in the wet lab at the back of the boat, an unbelievable amount of water was being filtered, bottled and identified for future analysis. We would often find Lauri Corlett and Claudie Meilleur, from the University of Manitoba and the Université de Sherbrooke, respectively, standing in the same spot and processing samples for hours on end. Elizabeth Kitching (a master’s student University of Manitoba) would be hiding in her environmental chamber, where the green light that provided controlled conditions for her research gave her an eerie, edgy aura.

To complement the offshore work done on the vessel, one of the zodiacs would be off most days doing work closer to the coast. For each of the zodiac stations, they would deploy a handheld castable CTD (an instrument that measures salinity, temperature and depth of seawater), collect water at different depths, and filter samples on the boat for environmental DNA (molecular traces of different species found in the water). They would also deploy a remotely operated vehicle to look for kelp, grab and sieve sediments for bottom-dwelling animals, and haul a small net to collect biodiversity living in the water column, among many other tasks.

When we weren’t sampling, the vessel was in transit to the next station, meaning that the crew members would be working around the clock. During transit in James Bay, the CTD would be cast every 5 miles (or roughly every 45 minutes)—including during the night. Chief Scientist CJ Mundy from the University of Manitoba would stay up until 5 a.m., then be replaced by co-principal investigator Jens Ehn for a few hours while he slept. Water was also collected during transit time with a near-surface water sampling system.

As you can tell, there was very little down time from the data collection. Still, we shared fabulous meals prepared and served like clockwork by our cook, Billy Gaudet, watched the Olympics (including the women’s soccer gold medal win), and enjoyed many movie nights together (featuring classics such as She’s the Man, The Princess Bride and La La Land). Other highlights of the expedition include swimming in James Bay and answering questions from social media users while hiding from a storm! Furthermore, we were delighted to witness a polar bear swimming off the coast of eastern James Bay. Luckily, none of us were swimming at the time.

Some of us were also fortunate enough to visit Moose Factory, a small community at the southern edge of James Bay, on August 9. That day, the Mushkegowuk Council and Environment and Climate Change Minister Jonathan Wilkinson announced the launch of a feasibility assessment for the establishment of a National Marine Conservation Area in western James Bay and southwestern Hudson Bay. The assessment includes funding for the gathering of traditional knowledge, which will be essential alongside scientific data to guide the management of the region.

With samples to process, data to analyze, and interest from the communities living around the bay, the research and crew teams are confident that the expedition was a success and are excited to return for more work next summer. To learn more about the participants of the James Bay 2021 expedition, visit our YouTube channel where we have posted videos presenting the researchers and their science. Stay tuned for more information, results and events!

Maude Durand is an Arctic Project Specialist with Oceans North.